Perspicuity is a fancy word for “clearness” / ease of understanding of Scripture. Carmen Bryant is a Baptist missionary and Bible scholar (M.A. and Th.M. from Western Seminary). Her words will be in blue.

*****

A study of the development of the doctrine Perspicuity of Scripture will show that it was not a teaching invented during the Protestant Reformation but a resurrected one.

In looking at this doctrine in church history, it is of paramount importance to recognize that in spite of its name, Perspicuity does not mean that there is nothing obscure in Scripture. The reasons for labeling the doctrine Perspicuity of Scripture are more historical than lexicographical. In addition to whatever internal obscurity might already exist, there were external conditions imposed on Scripture that resulted in its meaning being almost totally hidden to the Christian population.

In the Church of New Testament times, Perspicuity of Scripture was assumed, not debated. The apostles used the Old Testament Scriptures to validate their message that Jesus of Nazareth was the promised Messiah. Such a methodology could succeed because God’s message in Scripture was in fact clear to the listener.

In that way they were again of one mind with the Fathers and Catholic methodology, which stresses apostolic succession and continuity of developing Christian doctrine, derived from the original deposit of faith. Thirdly, they did not deny the absolute necessity of a visible, institutional Church with real authority. So on all these counts, the analogy of the NT writers citing the OT is far more in line with Catholicism than Protestantism.

The apostles could reason with their listeners by appealing to Scriptures they already knew and understood. In this the apostles followed the same methodology as their Master, who repeatedly referred to the teachings of the Hebrew Scriptures in order to back up his own. Jesus rebuked his listeners for having trouble understanding him — not because they could not understand the words he was saying but because they were spiritually unprepared. The words were clear enough, but their hearts belonged to Satan and could not receive Jesus’ teachings.

*

Similarly, the apostles and other leaders of the newly founded Church used the narratives, prophecies and wisdom literature of the Old Testament to convict both Jews and Gentiles of eternal truth. They expected their readers and listeners to understand not just the mere statements but also their spiritual significance. Spiritual understanding is a gift from God to all who are redeemed, a gift that is expected to grow to completeness, even to the point of fathoming the treasures of wisdom and knowledge that are in Christ. Believers who remain at the elementary level are rebuked. The apostles were operating on the principles of Perspicuity: all those who truly belong to God are expected to grow in their understanding of what is revealed in Scripture because of the work of God’s Spirit within. Unbelievers, on the other hand, are limited in their understanding because their hearts are not prepared to receive spiritual wisdom.

*

When the first post-apostolic authors cited Scripture, they were still referring primarily to the Septuagint version of the Hebrew Bible. Copies of the gospels and epistles circulated among the churches and were considered authoritative as Scripture if genuinely apostolic, but no one had yet gathered these documents into a cohesive collection. The writings of this period were aimed principally at combating false doctrine, especially Gnosticism, that was threatening the purity of the faith as handed down by the apostles. Although a complete doctrine of the Perspicuity of Scripture was not formulated until centuries later, we can still determine what the early writers believed about Perspicuity by observing the way they used Scripture in their fight against the aberrant beliefs that arose under the name of Christianity.

How do we know that what the church says is true? The Roman Catholic answer to this question is the clearest answer that has ever been formulated . . .

The ‘Roman Catholic consequences’ begin to emerge with the assertion that the Church, through its bishops, is the guardian of tradition. The task of the church is to see that the gospel is handed down without being corrupted. Since not all the nuances of the faith are explicitly developed in the Bible, it is the contribution of tradition to take what is only implicit in Scripture, and make it explicit in the church. Thus tradition is creative and dynamic, and the church sees to it that tradition neither contradicts itself nor becomes inconsistent with the Biblical witness. This means that Scripture and tradition are two sources of truth and must not be separated. If they are, so the view maintains, disaster follows. The Reformers asserted that tradition had distorted the Biblical witness . . .Roman Catholics believe, more fervently than Protestants imagine, that Scripture and tradition are complementary rather than antithetical sources of truth. (Robert McAfee Brown, The Spirit of Protestantism, Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1961, 172-173, 214)

A Bible-only mentality virtually equates spiritual reality with the text of Scripture itself, whereas the Scripture is a pointer to or a witness to that reality . . . There is a difference between being biblical and biblicistic (i.e., employing the Bible-only mentality). There is a difference between honoring ‘sola scriptura’ and bibliolatry (the excess veneration of Scripture). . . . On more than one occasion it has been pointed out that the Bible-only view of Scripture is very much like the Muslim view of Scripture . . . Muslims believe that the earthly Qu’ran is a perfect copy of an actual Qu’ran in Paradise . . . The Christian view of Scripture is that there is a human and historical dimension to Scripture . . . Scripture is not the totality of all God has said and done in this world. Scripture is that part of revelation and history specially chosen for the life of the people of God through centuries. ‘Sola scriptura’ means that the canon of Scripture is the final authority in the church; it does not claim to be the record of all God has said and done . . . Patient research in the matter of tradition has brought to the surface the good side of the concept. Paul himself uses the language of tradition in a good sense (1 Cor. 11:23, 15:3). Both Roman Catholic and Protestant scholars have been coming closer and closer in a newer and better notion of tradition on both sides. For example, they agree that much of the revelation given in the period of time contained in the Book of Genesis must have been carried on as tradition . . . In the Christian period the bridge between Christ and the written documents of the New Testament was certainly tradition. The ‘sola scriptura’ of the Reformers did not mean a total rejection of tradition. It meant that only Scripture had the final word on a subject . . . If we reject church tradition we have no idea what the New Testament is attempting to communicate. There is no question that the great majority of American evangelicals are not happy to have such a large weight given to tradition. Even so . . . might we not be heirs of tradition in such a manner that we are not aware of it? However we vote on this issue, it remains true that scholars no longer can talk about Scripture and totally ignore tradition . . . If a Christian could not have his own Scripture until the time of printing and its translation into modern languages, then the kind of Christianity the Bible-only mentality accepts could not have existed until the sixteenth century . . . If copies of the Holy Scripture were rare because of the expensive cost of reproduction by hand-copying then there must have been other valid sources through which the laymen could know the contents of the Christian faith. Such may be: the preaching of the bishop in the early church . . . ; the sacraments and the liturgy which used biblical themes, biblical personalities, and quotations from Scripture so that solid biblical truth could be learned indirectly . . . ; church architecture, decorations within a church, and other forms of Christian art which reflected biblical themes and materials. This is not an exhaustive list but it does show how the millions of Christians . . . could have had a substantial understanding of the Christian faith prior to the invention of printing. And if one has such a perspective on the whole history of the church he need not be caught in the logical box to which the Bible-only mentality leads . . . so narrow that it becomes self-defeating. (Bernard Ramm, in Rogers, Jack B., editor, Biblical Authority, Waco, Texas: Word Books, 1977, “Is ‘Scripture Alone’ the Essence of Christianity?’, 116-17, 119, 121-122)

The ‘sola scriptura’ principle does not exclude a respectful listening to the wisdom of the past. For we stand in a community of faith and cannot leap over two thousand years of Christian history in disregard of the prodigious labors already done . . . Biblicism is an antitraditional preoccupation with the Bible. It limits its interests to the Bible alone and does not seek nor accept the guidance and correction which the history of exegesis affords. There is something audacious about such a leap from the twentieth century back into the first century without even a glance at the ways in which Scripture has hitherto been understood. Indeed, in such a case there is the real danger that the interpreter will bring the Bible under his own control. Every explicit denial of tradition involves a hidden commitment to a personal brand of tradition. (Clark Pinnock, Biblical Revelation, Chicago: Moody Press, 1971, 118-119)

As regards the pre-Augustinian Church, there is in our time a striking convergence of scholarly opinion that Scripture and Tradition are for the early Church in no sense mutually exclusive: kerygma, Scripture and Tradition coincide entirely. The Church preaches the kerygma which is to be found in toto in written form in the canonical books.

The Tradition is not understood as an addition to the kerygma contained in Scripture but as the handing down of that same kerygma in living form: in other words everything is to be found in Scripture and at the same time everything is in the living Tradition. It is in the living, visible Body of Christ, inspired and vivified by the operation of the Holy Spirit, that Scripture and Tradition coinhere . . . Both Scripture and Tradition issue from the same source: the Word of God, Revelation . . . Only within the Church can this kerygma be handed down undefiled . . . (Heiko Oberman, The Harvest of Medieval Theology, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, revised 1967 edition, 366-367)

Clearly it is an anachronism to superimpose upon the discussions of the second and third centuries categories derived from the controversies over the relation of Scripture and tradition in the 16th century, for ‘in the ante-Nicene Church . . . there was no notion of sola Scriptura, but neither was there a doctrine of traditio sola.’. . . (1)

The apostolic tradition was a public tradition . . . So palpable was this apostolic tradition that even if the apostles had not left behind the Scriptures to serve as normative evidence of their doctrine, the church would still be in a position to follow ‘the structure of the tradition which they handed on to those to whom they committed the churches (2).’ This was, in fact, what the church was doing in those barbarian territories where believers did not have access to the written deposit, but still carefully guarded the ancient tradition of the apostles, summarized in the creed . . . The term ‘rule of faith’ or ‘rule of truth’ . . . seems sometimes to have meant the ‘tradition,’ sometimes the Scriptures, sometimes the message of the gospel . . . In the . . . Reformation . . . the supporters of the sole authority of Scripture . . . overlooked the function of tradition in securing what they regarded as the correct exegesis of Scripture against heretical alternatives. (Jaroslav Pelikan, The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine: Vol. 1 of 5: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600), Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1971, 115-17, 119; citations: 1. In Cushman, Robert E. and Egil Grislis, editors, The Heritage of Christian Thought: Essays in Honor of Robert Lowry Calhoun, New York: 1965, quote from Albert Outler, “The Sense of Tradition in the Ante-Nicene Church,” 29. 2. St. Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 3:4:1)

It should be unnecessary to accumulate further evidence. Throughout the whole period Scripture and tradition ranked as complementary authorities, media different in form but coincident in content. To inquire which counted as superior or more ultimate is to pose the question in misleading terms. If Scripture was abundantly sufficient in principle, tradition was recognized as the surest clue to its interpretation, for in tradition the Church retained, as a legacy from the apostles which was embedded in all the organs of her institutional life, an unerring grasp of the real purport and meaning of the revelation to which Scripture and tradition alike bore witness. (J. N. D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1978, 47-48)

[E]ven though the Catholic Church and the early Fathers admit a material sufficiency of the Bible it maintains that Tradition, Church and Scripture are inseparable…and that the one cannot understand the meaning of the Sacred Scripture without Tradition and Church! That is why the early Fathers can admit a sufficiency of the Bible and the existence of unwritten traditions at the same time….In sum, the Fathers admitted a material sufficiency of the Bible but no less affirmed its formal ‘insufficiency’! All things can be found within the pages of Holy Writ (implicitly or explicitly) but for a proper and authentic understanding of Scripture something else is required–that is, Tradition and Church.*Vincent of Lerins make the same point. We read in his Commonitories:*Here perhaps, someone may ask: Since the canon of the Scripture is complete and more than sufficient in itself, why is it necessary to add to it the authority of ecclesiastical interpretation? As a matter of fact, [we must answer] Holy Scripture, because of its depth, is not universally accepted in one and the same sense. The same text is interpreted different by different people, so that one may almost gain the impression that it can yield as many different meanings as there are men. Novatian, for example, expounds a passage in one way; Sabellius, in another; Donatus, in another. Arius, and Eunomius, and Macedonius read it differently; so do Photinus, Apollinaris, and Priscillian; in another way, Jovian, Pelagius, and Caelestius; finally still another way, Nestorius. Thus, becuase of the great distortions caused by various errors, it is, indeed, necessary that the trend of the interpretation of the prophetic and apostolic writings be directed in accordance with the rule of the ecclesiastical and Catholic meaning. (Comm 2)*. . . The point of controversy in these set of replies is this: did the Fathers affirm the Catholic rule of faith consisting of Scripture, Tradition and Church or did they affirm the Protestant rule of faith (Sola Scriptura) which interprets Scripture via private exegesis?*. . . the Catholic Church affirms and admits the ‘material’ sufficiency (apart from the canonical issues of the Bible) of both the Scriptures itself and Tradition itself….both have the same Divine origin and but differ in modes only…. That is why the Catholic Church will NOT base a doctrine (apart from canon of the Bible) only on tradition alone or on Scripture alone–the belief must find a touchstone in both! For example, in Ott’s “Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma” you will find Ott religiously appealing to BOTH Scripture and Tradition. All doctrines of the Catholic faith are found explicitly or implicitly in the pages of Holy Writ…the same goes for Tradition. Tradition has some advantages (there are others): 1) it permits fullness, which the written text would have narrowed down to the limits of clear exposition and 2) it is by it’s nature a community phenomenon — whereas the text could be read by an individual by him or herself, tradition by it’s very nature fufills the communal aspects of Church. Scripture too has some advantages(there are others): 1) has the dignity which always and everywhere has gained for itself, 2) contain the actual words of Our Lord and Savior, and 3) It is fixed under one cover. In sum, Tradition allows the Church to preserve God’s saving Word in it’s fullness while Scripture ensures the preservation of it’s purity! (From the web page St. Athanasius, the Scriptures, Tradition, and the Church (Joe Gallegos vs. James White), an excellent debate highly-related to the present one. See also Joe Gallegos’ page Material Sufficiency and Sola Scriptura in the Fathers (Contra William Webster) )

Clement, bishop of Rome in the last decade of the first century, frequently cites the Old Testament in his letter to the Corinthians about 96 AD. He does not explain the cited passage but assumes that his readers will understand the plain sense of the words and agree with his use of it . . . Scripture is plain enough to be understood and applied by all.

Let us conform to the glorious and holy rule of our tradition. (Letter to Corinthians 7:2)

- *

- But if certain people should disobey what has been said by him through us, let them understand that they will entangle themselves in no small sin and danger. (59:1)

. . . Irenaeus acknowledges that “simple-minded” people can be led astray by such twisting of Scripture, but only because these persons do not know enough of Scripture to keep them from being deceived. When the various passages are put back in their right order and context, the sense is clear to the one who has accepted the truth “received at baptism.”

In like manner he also who retains unchangeable — in his heart the rule of the truth which he received by means of baptism, will doubtless recognise the names, the expressions, and the parables taken from the Scriptures, but will by no means acknowledge the blasphemous use which these men make of them. But when he has restored every one of the expressions quoted to its proper position, and has fitted it to the body of the truth, he will lay bare, and prove to be without any foundation, the figment of these heretics.

. . . Thus Irenaeus sets forth and practices another principle of the doctrine of Perspicuity of Scripture that was to be stated more formally in later times: What is obscure in one portion of Scripture is made clear in another portion. The explanations of the more obscure portions are within Scripture itself. The believer needs to study and meditate upon the entire Word in order to find the sense that God intended.

Irenaeus interprets types, symbols and parables with Christ as the center of his hermeneutic. For him, the true interpretation of the Scriptures lies with the Church, because the Church has inherited its doctrines from the apostles of Christ. In the context of Against Heresies, the Church stands in contrast to those who have broken away from the mainstream, the Gnostic heretics that have either twisted Scripture or done away with the portions that are not suitable to their doctrine. There is no differentiation made among persons within the Church that would indicate some are qualified to read and interpret Scripture while others should be hindered. All are encouraged to learn, and the amount of understanding will vary with the study and meditation given to the Scripture — as well as the measure of love that a person has for God.

When, however, they are confuted from the Scriptures, they turn round and accuse these same Scriptures, as if they were not correct, nor of authority, and [assert] that they are ambiguous, and that the truth cannot be extracted from them by those who are ignorant of tradition . . . It comes to this, therefore, that these men do now consent neither to Scripture or tradition. (Against Heresies 3, 2:1)

Suppose there arise a dispute relative to some important question among us, should we not have recourse to the most ancient Churches with which the apostles held constant intercourse, and learn from them what is certain and clear in regard to the present question? For how should it be if the apostles themselves had not left us writings? Would it not be necessary, [in that case,] to follow the course of the tradition which they handed down to those to whom they did commit the Churches? (Against Heresies 3, 4:1)*But, again, when we refer them to that tradition which originates from the apostles, [and] which is preserved by means of the successions of presbyters in the Churches, they object to tradition, saying they themselves are wiser. (Against Heresies 3, 2:2)

For Irenaeus, on the other hand, tradition and scripture are both quite unproblematic. They stand independently side by side, both absolutely authoritative, both unconditionally true, trustworthy, and convincing.Irenaeus and Tertullian point to the church tradition as the authoritative locus of the unadulterated teaching of the apostles, they cannot longer appeal to the immediate memory, as could the earliest writers. Instead they lay stress on the affirmation that this teaching has been transmitted faithfully from generation to generation. One could say that in their thinking, apostolic succession occupies the same place that is held by the living memory in the Apostolic Fathers.

*

Next, it is argued that the exegetical School of Alexandria, and Fathers such as Clement of Alexandria and Origen, following Philo and Platonic thought, introduced foreign Greek philosophies into biblical commentary and hermeneutics, thus poisoning the well for perspicuity and popular understanding of the “clear” Scripture for subsequent generations throughout the Middle Ages until Luther and Calvin restored the true belief once again:

Origen further developed what was begun by Clement. Origen is especially significant because his allegorical methods established the hermeneutical methodology for the Church throughout the Middle Ages, and to some extent even to the present. Origen was also from Alexandria and a controversial figure even in his own time. He combined his Platonic philosophy with Christianity, particularly in the interpretation of Scripture, applying a body-soul-spirit theory to the Word of God. Many of the narratives were impossible happenings in his view. If Scripture really was divine literature, such narratives had to have a spiritual or mystical meaning. He did not completely do away with the literal, but nevertheless put his emphasis upon the spiritual.

. . . However, which narratives were to be understood literally, and which ones only spiritually? The logical outcome of this method would be the giving over to the trained leadership of the Church the responsibility to hear, read and study the Scriptures. Origen’s interpretative methods obscured much of Scripture and removed the possibility of profitable study for the average “untrained” Christian who would not be able to discern “literal narrative” from “spiritual narrative.”

The Fathers of the Church were not blind to the fact that the literal sense in some Scripture passages appears to imply great incongruities, not to say insuperable difficulties. On the other hand, they regarded the language of the Bible as truly human language, and therefore always endowed with a literal sense, whether proper or figurative. Moreover, St. Jerome (in Is., xiii, 19), St. Augustine (De tent. Abrah. serm. ii, 7), St. Gregory (Moral., i, 37) agree with St. Thomas (Quodl., vii, Q. vi, a. 14) in his conviction that the typical sense is always based on the literal and springs from it. Hence if these Fathers had denied the existence of a literal sense in any passage of Scripture, they would have left the passage meaningless. Where the patristic writers appear to reject the literal sense, they really exclude only the proper sense, leaving the figurative.*Origen (De princ., IV, xi) may be regarded as the only exception to this rule; since he considers some of the Mosaic laws as either absurd or impossible to keep, he denies that they must be taken in their literal sense. But even in his case, attempts have been made to give to his words a more acceptable meaning (cf. Vincenzi, “In S. Gregorii Nysseni et Origenis scripta et doctrinam nova recensio”, Rome, 1864, vol. II, cc. xxv-xxix). The great Alexandrian Doctor distinguishes between the body, the soul, and the spirit of Scripture. His defendants believe that he understands by these three elements its proper, its figurative, and its typical sense respectively. He may, therefore, with impunity deny the existence of any bodily sense in a passage of Scripture without injury to its literal sense. But it is more generally admitted that Origen went astray on this point, because he followed Philo’s opinion too faithfully. . . . It was Origen, too, who fully developed the hermeneutical principles which distinguish the Alexandrian School, though they are not applied in their entirety by any other Father.

The typical sense has its name from the fact that it is based on the figurative or typical relation of Biblical persons, or objects, or events, to a new truth. This latter is called the antitype, while its Biblical correspondent is named the type. The typical sense is also called the spiritual, or mystical, sense: mystical, because of its more recondite nature; spiritual, because it is related to the literal, as the spirit is related to the body. What we call type is called shadow, allegory, parable, by St. Paul (cf. Rom., v, 14; I Cor., x, 6; Heb., viii, 5; Gal, iv, 24; Heb., ix, 9); once he refers to it as antitype (Heb., ix, 24), though St. Peter applies this term to the truth signified (I Pet., iii, 21) . . .*Scripture and tradition agree in their testimony for the occurrence of the typical sense in certain passages of the Old Testament. Among the Scriptural texts which establish the typical sense, we may appeal to Col., ii, 16-17; Heb., viii, 5; ix, 8-9; Rom., v, 14; Gal., iv, 24; Matt., ii, 15 (cf. Os., xi, 1); Heb., i, 5 (cf. II K., vii, 14). The testimony of tradition concerning this subject may be gathered from Barnabas (Ep., 7, 8, 9, 12, etc.), St. Clement of Rome (I Cor., xii), St. Justin, Dial. c. Tryph., civ, 42), St. Irenaeus (Adv. haer., IV, xxv, 3; II, xxiv, 2 sqq.; IV, xxvi, 2), Tertullian (Adv. Marc., V, vii); St. Jerome (Ep. liii, ad Paulin., 8), St. Thomas (I, Q. i, a. 10), and a number of other patristic writers and Scholastic theologians. That the Jews agree with the Christian writers on this point, may be inferred from Josephus (Antiq., XVII, iii, 4; Pro m. Antiq., n. 4; III, vi, 4, 77; De bello Jud., V, vi, 4), the Talmud (Berachot, c. v, ad fin.; Quiddus, fol. 41, col. 1), and the writings of Philo (de Abraham; de migrat. Abraham; de vita contempl.), though this latter writer goes to excess in the allegorical interpretation . . .*All Catholic interpreters readily grant that in some passages of the Old Testament we have a typical sense besides the literal; but this does not appear to be granted with regard to the New Testament, at least not subsequently to the death of Jesus Christ. Distinguishing between the New Testament as it signifies a collection of books, and the New Testament as it denotes the Christian economy, they grant that there are types in the New-Testament books, but only as far as they refer to the pre-Christian economy. For the New Testament has brought us the reality in place of the figure, light in place of darkness, truth in place of shadow (cf. Patrizi, “De interpretatione Scripturarum Sacrarum”, p. 199, Rome, 1844). On the other hand, it is urged that the New Testament is the figure of glory, as the Old Testament was the figure of the New (St. Thom., Summa, I, Q. i, a. 10).*Again, in Scripture the literal sense applies to what precedes, the typical to what follows. Now, even in the New Testament Christ and His Body precedes the Church and its members; hence, what is said literally of Christ or His Body, may be interpreted allegorically of the Church, the mystical body of Christ, tropologically of the virtuous acts of the Church’s members, anagogically of their future glory (St. Thom., Quodl., VII, a. 15, ad 5um). Similar views are expressed by St. Ambrose (in Ps. xxx, n. 25), St. Chrysostom (in Matt., hom. lxvi), St. Augustine (in Joh., ix), St. Gregory the Great (Hom. ii, in evang. Luc., xviii), St. John Damascene (De fide orth., iv, 13); besides, the bark of Peter is usually regarded as a type of the Church, the destruction of Jerusalem as a type of the final catastrophe. . . .*

It may be said in general that these earliest Christian writers admitted both the literal and the allegorical sense of Scripture. The latter sense appears to have been favoured by St. Clement of Rome, Barnabas, St. Justin, St. Irenaeus, while the literal seems to prevail in the writings of St. Hippolytus, Tertullian, the Clementine Recognitions, and among the Gnostics. . . . Among the eminent writers of the Alexandrian School must be classed Julius Africanus (c. 215), St. Dionysius the Great (d. 265), St. Gregory Thaumaturgus (d. 270), Eusebius of Caesarea (d. 340), St. Athanasius (d. 373), Didymus of Alexandria (d. 397), St. Epiphanius (d. 403), St. Cyril of Alexandria (d. 444), and finally also the celebrated Cappadocian Fathers, St. Basil the Great (d. 379), St. Gregory Nazianzen (d. 389), and St. Gregory of Nyssa (d. 394). The last three, however, have many points in common with the School of Antioch. . . .

*

(c) The Latin Fathers. The Latin Fathers, too, admitted a twofold sense of Scripture, insisting variously now on the one, now on the other. We can only enumerate their names: Tertullian (b. 160), St. Cyprian (d. 258), St. Victorinus (d. 297), St. Hilary (d. 367), Marius Victorinus (d. 370), St. Ambrose (d. 397), Rufinus (d. 410), St. Jerome (d. 420), St. Augustine (d. 430), Primasius (d. 550), Cassiodorus (d. 562), St. Gregory the Great (d. 604). St. Hilary, Marius Victorinus, and St. Ambrose depend, to a certain extent, on Origen and the Alexandrian School; St. Jerome and St. Augustine are the two great lights of the Latin Church on whom depend most of the Latin writers of the Middle Ages. . . .

*

(ii) Second Period of Exegesis, A.D. 604-1546

*

We consider the following nine centuries as one period of exegesis, not on account of their uniform productiveness or barrenness in the field of Biblical study, nor on account of their uniform tendency of developing any particular branch of exegesis, but rather on account of their characteristic dependence on the work of the Fathers. Whether they synopsized or amplified, whether they analysed or derived new conclusions from old premises, they always started from the patristic results as their basis of operation.

Some of the expressions are so obscure as to shroud the meaning in the thickest darkness. And I do not doubt that all this was divinely arranged for the purpose of subduing pride by toil, and of preventing a feeling of satiety in the intellect, which generally holds in small esteem what is discovered without difficulty.

Accordingly the Holy Spirit has, with admirable wisdom and care for our welfare, so arranged the Holy Scriptures as by the plainer passages to satisfy our hunger, and by the more obscure to stimulate our appetite. For almost nothing is dug out of those obscure passages which may not be found set forth in the plainest language elsewhere.

For among the things that are plainly laid down in Scripture are to be found all matters that concern faith and the manner of life. After this, when we have made ourselves to a certain extent familiar with the language of Scripture, we may proceed to open up and investigate the obscure passages, and in doing so draw examples from the plainer expressions to throw light upon the more obscure, and use the evidence of passages about which there is no doubt to remove all hesitation in regard to the doubtful passages.

This is a dangerous practice. For it is far safer to walk by the light of Holy Scripture; so that when we wish to examine the passages that are obscured by metaphorical expressions, we may either obtain a meaning about which there is no controversy, or if a controversy arises, may settle it by the application of testimonies sought out in every portion of the same Scripture.

*

Here, the Protestant “either/or” mentality is fully apparent. Neither the centrality or popular “accessibility” of Scripture nor a respect for the literal hermeneutical sense rules out Tradition and Church, apostolic succession, or four-fold interpretation of Scripture. St. Augustine is not a Protestant!

If one cites him — as above — only when he agrees or appears to agree with one or more Protestant distinctives, but neglects to take into account numerous other statements of his which are entirely “Catholic,” then it is an improperly selective and ultimately intellectually dishonest presentation, and does disservice both to St. Augustine and the Protestant cause – supposedly so rooted in the early Church and the great Augustine himself. In this vein, Protestant scholar Heiko Oberman observes:

- Augustine . . . reflects the early Church principle of the coinherence of Scripture and Tradition. While repeatedly asserting the ultimate authority of Scripture, Augustine does not oppose this at all to the authority of the Church Catholic . . . The Church has a practical priority . . .

-

- But there is another aspect of Augustine’s thought . . . we find mention of an authoritative extrascriptural oral tradition. While on the one hand the Church ‘moves’ the faithful to discover the authority of Scripture, Scripture on the other hand refers the faithful back to the authority of the Church with regard to a series of issues with which the Apostles did not deal in writing. Augustine refers here to the baptism of heretics . . . (

The Harvest of Medieval Theology,

- Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, revised edition, 1967, 370-371)

[T]he custom [of not rebaptizing converts] . . . may be supposed to have had its origin in Apostolic Tradition, just as there are many things which are observed by the whole Church, and therefore are fairly held to have been enjoined by the Apostles, which yet are not mentioned in their writings. (On Baptism, Against the Donatists 5:23[31] [A.D. 400] )*But the admonition that he [Cyprian] gives us, ‘that we should go back to the fountain, that is, to Apostolic Tradition, and thence turn the channel of truth to our times,’ is most excellent, and should be followed without hesitation. (Ibid., 5:26[37] )*But in regard to those observances which we carefully attend and which the whole world keeps, and which derive not from Scripture but from Tradition, we are given to understand that they are recommended and ordained to be kept, either by the Apostles themselves or by plenary [ecumenical] councils, the authority of which is quite vital in the Church. (Letter to Januarius [A.D. 400])*For in the Catholic Church, not to speak of the purest wisdom, to the knowledge of which a few spiritual men attain in this life, so as to know it, in the scantiest measure, indeed, because they are but men, still without any uncertainty…The consent of peoples and nations keep me in Church, so does her authority, inaugurated by miracles, nourished by hope, enlarged by love, established by age. The SUCCESSION of priests keeps me, beginning from the very seat of the APOSTLE PETER, to whom the Lord, after his resurrection, gave it in charge to feed his sheep, down to the present EPISCOPATE…The epistle begins thus: — ‘Manicheus, an apostle of Jesus Christ, by the providence of God the Father. These are the wholesome words from the perennial and living fountain.’ Now, if you please, patiently give heed to my inquiry. I do not believe Manichues to be an apostle of Christ. Do not, I beg you, be enraged and begin to curse. For you know that it is my rule to believe none of your statements without consideration. Therefore I ask, who is this Manicheus? You will reply, An Apostle of Christ. I do not believe it. Now you are at a loss what to say or do; for you promised to give knowledge of truth, and here you are forcing me to believe what I have no knowledge of. Perhaps you will read the gospel to me, and will attempt to find there a testimony to Manicheus. But should you meet with a person not yet believing in the gospel, how would you reply to him were he to say, I do not believe? For MY PART, I should NOT BELIEVE the gospel except moved by the authority of the Catholic Church. So when those on whose authority I have consented to believe in the gospel tell me not to believe in Manicheus, how can I BUT CONSENT? (C. Epis Mani 5,6)*Wherever this tradition comes from, we must believe that the Church has not believed in vain, even though the express authority of the canonical scriptures is not brought forward for it. (Letter 164 to Evodius of Uzalis)

To be sure, although on this matter, we cannot quote a clear example taken from the canonical Scriptures, at any rate, on this question, we are following the true thought of Scriptures when we observe what has appeared good to the universal Church which the authority of these same Scriptures recommends to you. (C. Cresconius I: 33)

It is obvious; the faith allows it; the Catholic Church approves; it is true. (Sermon 117:6)

The authority of our Scriptures, strengthened by the consent of so may nations, and confirmed by the succession of the Apostles, bishops and councils, is against you. (C. Faustus 8:5)*No sensible person will go contrary to reason, no Christian will contradict the Scriptures, no lover of peace will go against the CHURCH. (Trinitas 4, 6, 10)

*

He considered Origen a heretic but also thought he had done a credible job of explaining some obscure passages of Scripture.

Jerome played an involuntary role in Scripture’s becoming concealed from the Christian population in ensuing centuries. He translated the Bible into Latin because Greek was no longer a lingua franca in Europe. The Vulgate was the result, appropriately named because it was written in the vulgar or common language of the time. Approximately 300-400 years later, though, Latin had gone through enough changes that people of southern and western Europe began to realize that the Classical Latin taught in the schools was “perceptibly a different language, rather than merely a more polished, cultured version of their own.”

In the meantime, the Vulgate became the recognized authoritative translation of the Scriptures for use in the Church of Rome. The sacredness ascribed to the Word of God was extended as well to the language into which it had been translated, i.e., the Latin that had become the official language of the Church. The attitude toward Latin was also affected by tradition. Since “the time of Saints Hilary and Augustine the notion prevailed that the three languages used in the inscription on the Cross [Aramaic, Latin and Greek] were sacred.” The common language continued to change over the centuries, but the language of the Church and the Word of God did not. The God who communicated with mankind to the point of incarnating himself in human flesh became a God who was steeped in mystery, his revelations known only to a select few.

This was not the intention of Jerome.

I will tell you my opinion briefly and without reserve. We ought to remain in that Church which was founded by the Apostles and continues to this day. If ever you hear of any that are called Christians taking their name not from the Lord Jesus Christ, but from some other, for instance, Marcionites, Valentinians, Men of the mountain or the plain, you may be sure that you have there not the Church of Christ, but the synagogue of Antichrist. For the fact that they took their rise after the foundation of the Church is proof that they are those whose coming the Apostle foretold. And let them not flatter themselves if they think they have Scripture authority for their assertions, since the devil himself quoted Scripture, and the essence of the Scriptures is not the letter, but the meaning. Otherwise, if we follow the letter, we too can concoct a new dogma and assert that such persons as wear shoes and have two coats must not be received into the Church. (The Dialogue Against the Luciferians 28)

*

Not all theologians in the early Church, however, agreed with this allegorical approach. Those of the Antiochene school dissented from the position that there was a spiritual meaning hidden within the text. In fact, they held that allegorical interpretation destroyed the real message of Scripture. They also distinguished between allegory as used in Scripture itself, and the allegorical interpretation as used by the Alexandrian school. They were unwilling to lose [the historical reality of the biblical revelation] in a world of symbols and shadows.Where the Alexandrines use the word theory as equivalent to allegorical interpretation, the Antiochene exegetes use it for a sense of scripture higher or deeper than the literal or historical meaning, but firmly based on the letter. This understanding does not deny the literal meaning of scripture but is grounded on it, as an image is based on the things represented and points toward it. Both image and thing are comprehensible at the same time. There is no hidden meaning which only a Gnostic can comprehend. John Chrysostom observes that everywhere in scripture there is this law, than when it allegorizes, it also gives the explanation of the allegory.”

Again, this was the mainstream patristic position, not just that of the School of Antioch.

. . . Even as the Alexandrians did not completely dispense with the literal meaning of Scripture, so also the Antiochenes did not dismiss allegory. However, they insisted that any allegorical interpretation must be based on the literal. The Antiochene school’s hermeneutic lost out to that of the Alexandrians. Their methods were not forgotten, however, and were later revived in the 13th century by St. Thomas Aquinas, who greatly admired the work of John Chrysostom and was responsible for restoring the literal meaning to its rightful importance.

I cite once more the online Catholic Encyclopedia article on Biblical Exegesis (by A. J. Maas; bolded emphasis added):

The School of Antioch. The Fathers of Antioch adhered to hermeneutical principles which insist more on the so-called grammatico-historical sense of the Sacred Books than on their moral and allegorical meaning. It is true that Theodore of Mopsuestia urged the literal sense to the detriment of the typical, believing that the New Testament applies some of the prophecies to the Messias only by way of accommodation, and that on account of their allegories the Canticle of Canticles, together with a few other books, should not be admitted into the Canon. But generally speaking, the Fathers of Antioch and Eastern Syria, the latter of whom formed the School of Nisibis or Edessa, steered a course midway between Origen and Theodore, avoiding the excesses of both, and thus laying the foundation of the hermeneutical principles which the Catholic exegete ought to follow. The principal representatives of the School of Antioch are St. John Chrysostom (d. 407); Theodore of Mopsuestia (d. 429), condemned by the Fifth Ecumenical Synod on account of his explanation of Job and the Canticle of Canticles, and in certain respects the forerunner of Nestorius; St. Isidore of Pelusium, in Egypt (d. 434), numbered among the Antiochene commentators on account of his Biblical explanations inserted in about two thousand of his letters; Theodoret, Bishop of Cyrus in Syria (d. 458), known for his Questions on the Octateuch, the Books of Kings and Par., and for his Commentaries on the Psalms, the Cant., the Prophets, and the Epistles of St. Paul. The School of Edessa glories in the names of Aphraates who flourished in the first half of the fourth century, St. Ephraem (d. 373), Cyrillonas, Balaeus, Rabulas, Isaac the Great, etc.

Several passages have occurred in the foregoing Chapters, which serve to suggest another principle on which some words are now to be said. Theodore’s exclusive adoption of the literal, and repudiation of the mystical interpretation of Holy Scripture, leads to the consideration of the latter, as one of the characteristic conditions or principles on which the teaching of the Church has ever proceeded. Thus Christianity developed, as we have incidentally seen, into the form, first, of a Catholic, then of a Papal Church.

*Now it was Scripture that was made the rule on which this development proceeded in each case, and Scripture moreover interpreted in a mystical sense; and, {339} whereas at first certain texts were inconsistently confined to the letter, and a Millennium was in consequence expected, the very course of events, as time went on, interpreted the prophecies about the Church more truly, and that first in respect of her prerogative as occupying the orbis terrarum, next in support of the claims of the See of St. Peter. This is but one specimen of a certain law of Christian teaching, which is this, – a reference to Scripture throughout, and especially in its mystical sense [Note 14].1. This is a characteristic which will become more and more evident to us, the more we look for it. The divines of the Church are in every age engaged in regulating themselves by Scripture, appealing to Scripture in proof of their conclusions, and exhorting and teaching in the thoughts and language of Scripture. Scripture may be said to be the medium in which the mind of the Church has energized and developed [Note 15]. When St. Methodius would enforce the doctrine of vows of celibacy, he refers to the book of Numbers; and if St. Irenaeus proclaims the dignity of St. Mary, it is from a comparison of St. Luke’s Gospel with Genesis. And thus St. Cyprian, in his Testimonies, rests the prerogatives of martyrdom, as {340} indeed the whole circle of Christian doctrine, on the declaration of certain texts; and, when in his letter to Antonian he seems to allude to Purgatory, he refers to our Lord’s words about “the prison” and “paying the last farthing.” And if St. Ignatius exhorts to unity, it is from St. Paul; and he quotes St. Luke against the Phantasiasts of his day. We have a first instance of this law in the Epistle of St. Polycarp, and a last in the practical works of St. Alphonso Liguori. St. Cyprian, or St. Ambrose, or St. Bede, or St. Bernard, or St. Carlo, or such popular books as Horstius’s Paradisus Animae, are specimens of a rule which is too obvious to need formal proof. It is exemplified in the theological decisions of St. Athanasius in the fourth century, and of St. Thomas in the thirteenth; in the structure of the Canon Law, and in the Bulls and Letters of Popes. It is instanced in the notion so long prevalent in the Church, which philosophers of this day do not allow us to forget, that all truth, all science, must be derived from the inspired volume. And it is recognized as well as exemplified; recognized as distinctly by writers of the Society of Jesus, as it is copiously exemplified by the Ante-nicene Fathers. . . . “Holy Scripture,” says Cornelius Lapide, “contains the beginnings of all theology: for theology is nothing but the science of conclusions which are drawn from principles certain to faith, and therefore is of all sciences most august as well as certain; but the principles of faith and faith itself doth Scripture contain; whence it evidently follows that Holy Scripture lays down those principles of theology by which the theologian begets of the mind’s reasoning his demonstrations. He, then, who thinks he can tear away Scholastic Science from the work of commenting on Holy Scripture is hoping for offspring without a mother.” [Note 19] Again: “What is the subject-matter of Scripture? Must I say it in a word? Its aim is de omni scibili; it embraces in its bosom all studies, all that can be known: and thus it is a certain university of sciences containing all sciences either ‘formally’ or ’eminently.'” [Note 20]

Nor am I aware that later Post-tridentine writers deny that the whole Catholic faith may be proved from Scripture, though they would certainly maintain that it is not to be found on the surface of it, nor in such sense that it may be gained from Scripture without the aid of Tradition. [Thus Newman confirms that Catholics acknowledge material sufficiency of Scripture] 2.

And this has been the doctrine of all ages of the Church, as is shown by the disinclination of her teachers to confine themselves to the mere literal interpretation of Scripture. Her most subtle and powerful method of proof, whether in ancient or modern times, is the mystical sense, which is so frequently used in doctrinal controversy as on many occasions to supersede any other.

Thus the Council of Trent appeals to the peace-offering spoken of in Malachi {343} in proof of the Eucharistic Sacrifice; to the water and blood issuing from our Lord’s side, and to the mention of “waters” in the Apocalypse, in admonishing on the subject of the mixture of water with the wine in the Oblation. Thus Bellarmine defends Monastic celibacy by our Lord’s words in Matthew xix., and refers to “We went through fire and water;” etc., in the Psalm, as an argument for Purgatory; and these, as is plain, are but specimens of a rule. Now, on turning to primitive controversy, we find this method of interpretation to be the very basis of the proof of the Catholic doctrine of the Holy Trinity. Whether we betake ourselves to the Ante-nicene writers or the Nicene, certain texts will meet us, which do not obviously refer to that doctrine, yet are put forward as palmary proofs of it. Such are, in respect of our Lord’s divinity, “My heart is inditing of a good matter,” or “has burst forth with a good Word;” “The Lord made” or “possessed Me in the beginning of His ways;” “I was with Him, in whom He delighted;” “In Thy Light shall we see Light;” “Who shall declare His generation?” “She is the Breath of the Power of God;” and “His Eternal Power and Godhead.”

On the other hand, the School of Antioch, which adopted the literal interpretation, was, as I have noticed above, the very metropolis of heresy. Not to speak of Lucian, whose history is but imperfectly known, (one of the first masters of this school, and also teacher of Arius and his principal supporters), Diodorus and Theodore of Mopsuestia, who were the most eminent masters of literalism in the succeeding generation, were, as we have seen, the forerunners of Nestorianism. The case had been the same in a still earlier age; — the Jews clung to the literal sense of the Scriptures and hence rejected the Gospel; the Christian Apologists proved its divinity by means of the allegorical. The formal connexion of this mode of interpretation with {344} Christian theology is noticed by Porphyry, who speaks of Origen and others as borrowing it from heathen philosophy, both in explanation of the Old Testament and in defence of their own doctrine.

It may be almost laid down as an historical fact, that the mystical interpretation and orthodoxy will stand or fall together. [Protestant Church historian Jaroslav Pelikan, in his The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600), p. 61 – cited earlier – quotes the last sentence above, in the course of a treatment of hermeneutics, and notes that “Newman’s generalization is probably an accurate one.”] This is clearly seen, as regards the primitive theology, by a recent writer, in the course of a Dissertation upon St. Ephrem. After observing that Theodore of Heraclea, Eusebius, and Diodorus gave a systematic opposition to the mystical interpretation, which had a sort of sanction from Antiquity and the orthodox Church, he proceeds; “Ephrem is not as sober in his interpretations, nor could it be, since he was a zealous disciple of the orthodox faith. For all those who are most eminent in such sobriety were as far as possible removed from the faith of the Councils”. On the other hand, all who retained the faith of the Church never entirely dispensed with the spiritual sense of the Scriptures. For the Councils watched over the orthodox faith; nor was it safe in those ages, as we learn especially from the instance of Theodore of Mopsuestia, to desert the spiritual for an exclusive cultivation of the literal method. Moreover, the allegorical interpretation, even when the literal sense was not injured, was also preserved; because in those times, when both heretics and Jews in controversy were stubborn in their objections to Christian doctrine, maintaining that the Messiah was yet to come, or denying the abrogation of the Sabbath and ceremonial law, or ridiculing the Christian doctrine of the Trinity, and especially that of Christ’s Divine Nature, under such circumstances ecclesiastical writers found it to their purpose, in answer to such exceptions, violently to refer {345} every part of Scripture by allegory to Christ and His Church.” [Note 21] . . . The use of Scripture then, especially its spiritual or second sense, as a medium of thought and deduction, is a characteristic principle of doctrinal teaching in the Church.

*

-

-

- Patriarch / Years / Heresy

-

- Paul of Samosata 260-269 Modalist

- Eulalius c.322 Arian

- Euphronius c.327-c.329 Arian

- Leontius 344-58 Arian

- Eudoxius 358-60 Arian

- Euzoius 361-78 Arian

- Peter the Fuller 470,475-7, 482-88 Monophysite

- John Codonatus 477,488 Monophysite

- Palladius 488-98 Monophysite

- Severus 512-18 Monophysite

- Sergius c.542-c.557 Monophysite

- Paul “the Black” c.557-578 Monophysite

- Peter Callinicum 578-91 Monophysite

- Anthanasius c.621-629 Monothelite

- Macedonius 640-c.655 Monothelite

- Macarius c.655-681 Monothelite

Nestorius (d.c. 451), from whom the heresy takes its name . . . entered a monastery at Antioch, where he became imbued with the principles of the Antiochene theological school, and probably studied under Theodore of Mopsuestia . . . Nestorius’s opponents succeeded in winning the support of St. Cyril of Alexandria and the Egyptian monks to their cause. Both sides having appealed to Rome, at a Council held there in August 430, Nestorius’s teaching was condemned by Pope Celestine.[and also in 431 by the Ecumenical Council of Ephesus which proclaimed in opposition that Mary was the “Mother of God” or “Theotokos,” not simply “Christotokos”] (F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, editors, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Oxford Univ. Press, 2nd ed., 1983, 961-962)

[I]ts soteriology . . . admitted a significant place to human merit. This fact may explain Nestorius’s sympathy for Pelagius.[it is also noted that Antioch’s Christological tendency “was towards Sabellianism”] (J. D. Douglas, editor, The New International Dictionary of the Christian Church, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Pub. House, revised edition of 1978, 49)

- “Therefore, brethren, stand fast and hold the traditions which you have been taught, whether by word or by our letter” [2 Thess 2:15]. From this it is clear that they did not hand down everything by letter, but there was much also that was not written. Like that which was written, the unwritten too is worthy of belief. So let us regard the tradition of the Church also as worthy of belief. Is it a tradition? Seek no further. (Homilies on 2 Thess 4:2)

Why promote the neo-Patristic approach? Meditation upon things said in Sacred Scripture is important for every Christian. The Fathers of the Church have laid out a basic Christian approach to the study and meditation of the inspired word. This approach of the Fathers was followed by all Catholic exegetes, especially as regards the literal sense, but in recent centuries with lessening emphasis upon the spiritual senses except for certain texts relating to the dogmas of the Church. However, towards the end of the nineteenth century some Catholic exegetes (interpreters) began to follow what is now known as the historical-critical approach, developed by rationalist and liberal Protestant exegetes, and this new approach has now with some exceptions virtually supplanted the Patristic approach among Catholic biblical scholars.*But many problems and logical contradictions have arisen from the results of historical-critical interpretation, even when used by Catholic exegetes. The neo-Patristic approach aims to address and solve these problems and contradictions and to reinstate the Patristic approach by the use of an updated framework based upon the largely implicit framework of the Fathers of the Church in the hope of enabling insights old and new and of making it easier to pray the Scriptures.. . . . The Patristic approach is recommended, if not mandated, in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (paragraphs 115-119). These paragraphs should be reread and discussed. They illustrate the need and the urgency of developing the neo-Patristic approach. . . .*

The neo-Patristic method uses the framework of the four senses of Sacred Scripture, as developed initially by St. Augustine of Hippo and others and more fully by St. Thomas Aquinas, especially in his Summa Theologiae (part I, question 1, article 10) See Thomas Kuffel, “St. Thomas’ Method of Biblical Exegesis,” in Living Tradition, no. 38 (November 1991). The four senses involved are the literal sense, the allegorical sense, the tropological, or moral, sense, and the anagogical, or eschatological, sense (also known as the final sense). These four senses will be examined in the course of this study program.

The neo-Patristic method, just as the Patristic method, always begins with the literal sense of a passage, which sense is basic to the three spiritual senses and can be understood to a degree without them, but, from a neo-Patristic viewpoint, it cannot be fully understood except in contrast with one or more of the spiritual senses which may be written with the same words into the same passage.

Importance of the literal sense. Pope Pius XII, in his encyclical letter Divino afflante Spiritu (Enchiridion biblicum, 550; Rome and the Study of Scripture, 550), points out to interpreters of the Sacred Books that “their foremost and greatest endeavor should be to discern and define clearly that sense of the biblical words which is called literal.” It is necessary to determine first what the sacred text really says before one can come to understand what the sacred text really means.

All of the truths that are necessary for faith are expressed or implied in the literal sense of Sacred Scripture or in the Sacred Tradition of the Church, and, we might add, the basic facts and truths that underlie the three spiritual senses of Sacred Scripture are all presented somewhere in the literal sense of the Scriptures or in the Sacred Tradition of the Church.

The neo-Patristic approach to historicity. While the historical-critical method tends to assume that accounts in the Sacred Scriptures are unhistorical in the modern sense, the neo-Patristic method assumes that Scriptural accounts presented as history are historical. This difference between the two methods arises historically from the fact that historical-criticism is rooted in rationalism, while the neo-Patristic method is rooted in belief that the Sacred Scriptures have been written by God through the human instrumentality of the sacred writers. The sacred writers were not used as subhuman instruments in the sense of automatic writing in which the human writer writes unconsciously under the influence of someone else, but through their use by the Holy Spirit as rational persons who were cooperating with their mind and will. In the neo-Patristic understanding of divine inspiration, what the sacred writers wrote was not limited entirely by their own background and personal capacities; they were not confined by their own knowledge and experience.

Thomas Aquinas, the “angelic doctor” of the Church, moved away from a reliance upon allegorical interpretation toward an appreciation of the literal meaning of Scripture. He still promoted allegory, dividing it into three possible meanings, but insisted that all allegorical interpretation must rise from the literal meaning, not apart from it. All these meanings are possible because God has the power to use human language and adapt it as needed for his own purposes.

Since the literal sense is that which the author intends, and since the author of Holy Writ is God, Who by one act comprehends all things by His intellect, it is not unfitting, as Augustine says (Confess. xii), if, even according to the literal sense, one word in Holy Writ should have several senses.

All of this was identical to the patristic consensus, and no different from the usual, normative approach of Catholicism throughout its entire history, so again, it looks like we are dealing here with a vast oversimplification, and a co-opting of St. Thomas as another sort of “proto-Protestant,” which is as ludicrous as when the same attempt is made to “claim” St. Augustine. The very fact that Protestants so admire Augustine and Aquinas and want so much to claim them for their camp (when in fact they are entirely Catholic, and the preeminent Catholic theologians) shows that something is strangely, ironically awry in the Protestant opinion of Catholicism, and that the Catholic Church throughout its history was far more “on the ball” than many Protestants are willing to admit.

- St. Thomas reflected on this method and gave a valuable explanation of the four senses in addition to expounding them in his commentaries on the Scriptures. His teaching can serve as the starting point for a more extended and differentiated exposition of this method, beginning with the first big distinction between the “literal” sense and the “spiritual,” or “mystical,” sense. For St. Thomas, this distinction arises from the fact that the rightly understood meaning of the words themselves of Sacred Scripture pertains to the literal, or historical, sense, while the fact that the things expressed by the words signify other things produces the spiritual sense. Thus, the spiritual sense is understood to be a typical, or figurative, sense which is based upon the literal sense and presupposes it. This basic double sense is possible because God, who is the principal Author of Sacred Scripture, has brought it about that things and events having their own historical meaning are used also to signify other things. But the central thing signified by these prefigurements is Jesus Christ Himself, who as the God-Man is the central focus of the spiritual sense and the subject of an extended symbolism which is known as the Allegory of Christ.The distinction between the literal and the spiritual senses of Sacred Scripture is analytical, even though spiritual realities are often the primary meaning of a text, because a certain interaction of faith and reason is implied in this division. The original meaning of words can be examined by unaided reason, as can the unfolding of visible happenings, but the spiritual meaning of words and events can be seen only by the light of faith. In Part I, Question I of the Summa Theologiae, St. Thomas points out that revealed teaching is necessary for man (article 1), that this teaching is a science based upon revealed truths that are visible under the light of faith (article 2), and that God is the subject of this science (article 7). Approaching, then, the distinction between the literal and the spiritual senses from an analytical point of view, I would say that the literal sense tends to be exclusively seen by the unaided human reason, while the spiritual sense is penetrated by theological reason aided by the light of faith. Where the text is speaking literally about spiritual realities, and above all about supernatural realities, the unaided reason can see the statement in a flattened and unmeaningful way, but it cannot “understand” the statement. Where the text contains spiritual meanings beneath the literal sense, the unaided reason can see these meanings at best in a flattened and unmeaningful way, while reason enlightened by faith can both see the spiritual meanings in a meaningful way and see the literal meaning in a more complete way – provided that it has the appropriate theological framework at its command. Looking, then, at sacred teaching as presented by the text of Sacred Scripture, and reasoning along the lines of St. Thomas, we can justifiably say that the inspired writings are necessary, not only because what is contained in them spiritually could not be figured out by man on his own, but also because the poor, fallen reason of man tends away from the spiritual truth and towards his own self-gratification. Men without grace do not want to know the spiritual truth and they endeavor to rub it out where it is written. But men possessed of faith and sanctifying grace will discover the truth and understand it. . . . St. Thomas answers affirmatively to the question “whether there ought to be distinguished four senses of Sacred Scripture,”34 basing his response upon the authority of St. Augustine of Hippo and of Venerable Bede. St. Augustine observed: “In all the holy books it is behooving to discern the eternal things to be seen there, the deeds that are there narrated, the future things that are predicted, the things that are commanded to be done.”35 St. Thomas sees these four things to refer respectively to the anagogical, the historical, the allegorical, and the tropological senses of Sacred Scripture. St. Thomas also quotes Venerable Bede as saying: “There are four senses of Sacred Scripture: history, which narrates things done; allegory, in which one thing is understood from another; tropology (that is, moral discourse), in which the ordering of habits is treated; and anagogy, by which we are led upward to treat of highest and heavenly things.”36 St. Thomas identifies the “historical sense” of Bede with the literal sense presented by the words themselves, and he makes an analytical division of the spiritual sense into allegory, tropology, and anagogy . . . . . . St. Thomas notes in the first place that things which actually happened can refer to Christ and his members as shadows of the truth, and this is what produces the allegorical sense, while other comparisons, being imaginary rather than real, whether in Sacred Scripture or in other literature, do not stand outside of the literal sense. Hence, the allegorical sense of Sacred Scripture is not imaginary and is not a genre of human inventiveness. . . . Finally, it might seem that, if these four senses were necessary for Sacred Scripture, each and every part of Sacred Scripture would have to have these four senses, but, as Augustine says in his commentary on Genesis, “in some parts the literal sense alone is to be sought.” To this St. Thomas replies that various parts of Scripture have four, three, two, or only one of these senses. Thus, the literal events of the Old Testament can be expounded in the four senses. The things spoken literally of Christ as the Head of the New Testament Church can also be expounded according to the four senses, because the historical Body of Christ can be expounded allegorically of the Mystical Body of Christ, and tropologically of the acts of the faithful to be modelled after the example of Christ, and anagogically inasmuch as Christ is the way to glory that has been shown to us. The things spoken literally of the Church of the New Testament can be expounded in three senses, because they can also be expounded tropologically and anagogically, but not allegorically, except that things mentioned literally regarding the primitive Church may have allegorical meaning regarding the later Church of the New Testament. The things of moral import in the literal sense can be expounded only literally and allegorically. And, finally, the things spoken literally regarding the state of glory cannot be expounded in any other sense.

***

(originally 6-11-00)

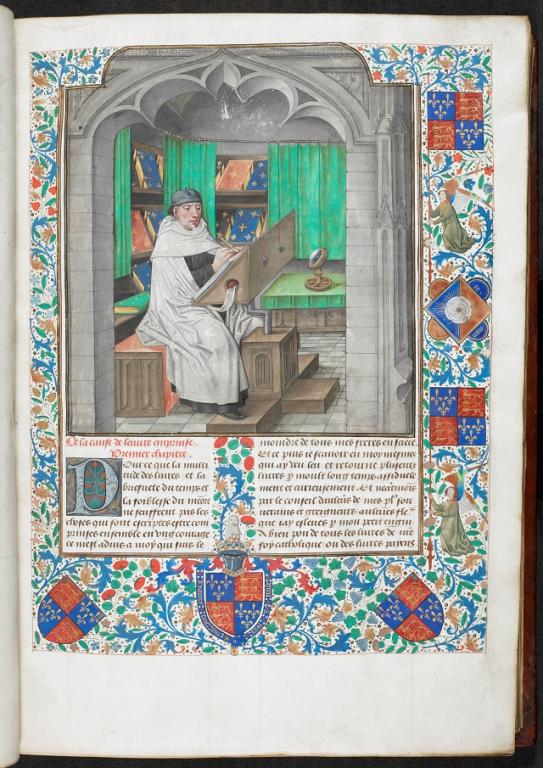

Photo credit: Miniature of the book’s author, Vincent of Beauvais, within a border containing the arms of Edward IV, to whom this manuscript belonged. Miroir historial, vol. 1 (Vincent of Beauvais, Speculum historiale, trans. into French by Jean de Vignay), Bruges, c. 1478-1480, Royal 14 E. i, vol. 1, f. 3r [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

Documentary Theory of Biblical Authorship (JEPD): Dialogue

* * * * *

God cannot act arbitrarily. That is blasphemy. So you are either questioning God or biblical inspiration. This incident is mentioned in Hebrews 11:17-19 and James 2:21. So do you now doubt the inspiration of the NT? Or do you simply pick and choose the verses you like and discard those that you don’t understand or don’t care for? Who is arbitrary now? Sounds like you, not our Lord God.

The moral lesson in Genesis, if there is one, is that we must always obey the dictates of conscience in absolute trust, and it this obedience that is credited to us as righteousness!

We must obey God, even though we don’t understand, yes. That’s what the book of Job is about. God has the power over life and death. Abraham could theoretically sacrifice his own son (but note that God didn’t really intend for this to happen, since He prevented it), because God the Father sacrificed His own Son.

I do not believe that Exodus and Genesis are written entirely by the same human author, or even in the same time period, which may be part of the confusion I see coming out over the high level exegesis I have already provided. I believe that there are different sources at work here, and though I am not a strict four-sourcer, I do find the J,P,E and D categories helpful to understanding a point I will make later.

I reject that, for various reasons, and think that it is fatal to solid exegesis. In a nutshell, what I would call the “liberal” exegete always has an “out” of simply denying that the text was in the original, or attributing it to one of the other “letter guys” (J,E,P,D), to explain all so-called “discrepancies.” Thus, a person is freed from the burden of trying to interpret the Bible as a harmonious whole: consistent with a notion of ultimate inspiration (being “God-breathed”). I find this to be absurd, because it is arbitrary in many ways, and most unfair (in a discussion such as this) to the exegete who accepts the entire Bible as inspired, and Genesis as written by one author originally (Moses).

The liberal is always a “moving target” (like the ducks in a carnival sideshow) whereas the Catholic who accepts the traditional dogma of inspiration is a “huge barn” or “sitting duck.” That destroys constructive exegetical dialogue. In a nutshell, what I would call the “liberal” exegete always has an “out” of simply denying that the text was in the original, or attributing it to one of the other “letter guys” (J,E,P,D), to explain all so-called “discrepancies.”

In exegeting the Genesis passage, I am not trying to start by presuming to know God is a consistent being who cannot contradict himself.

If the Bible is indeed inspired in toto, that would follow as a matter of course, would it not? The question isn’t whether theological and cultural understanding develops. It certainly does (and development of doctrine is my favorite topic in theology and one of my specialties — and indeed what made me a Catholic in large part). Rather, it is a fundamental question about the nature of revelation and inspiration. If one believes in those on other grounds, your premise above in how you approach the text is either irrelevant or meaningless. So we have fundamental disagreements.

Rather, I am saying I am going to approach this text as a piece of literature and try to determine what the human author intended.

That goes only so far. The danger is to reduce Holy Writ to a mere archaeological piece rather than God’s inspired, infallible, and inerrant revelation (all de fide dogmas, too, by the way, and not optional for an orthodox Catholic).

Only after making this determination, will I then move to the issue of what God might be saying to us today through this human author. I believe this approach is justified in Dei Verbum and in the Catechism. In Church teaching, the classical “literal sense” of Scripture is the meaning intended by the human author who wrote in idioms and forms common to his or her culture.

Again, that is true to a large extent, but it is distorted by being applied to the exclusion of the inspired and self-harmonious nature of the document (the Bible).

I gave several examples where the J source behind much of Genesis acts in ways we would consider arbitrary. One minute, Yahweh is telling Abraham to kill Isaac, the next he’s not.

This is a sterling example of the ludicrosity often involved in the adoption (or I should say, application) of the JEPD theory, or something akin to it. What you find “arbitrary” and objectionable is easily explained as a test where God knew all along that He would not actually require Abraham to do the act. That was understood not far from this time period by the Jews, as illustrated in the book of Job. They were not so stupid that they couldn’t figure it out. It is only modern liberal exegesis that reaches heights of (what Malcolm Muggeridge would call) “fathomless imbecility.”

And though Abraham committed murder in his heart, his faith in Yahweh is credited to him as righteousness.

This is absurd also, because if this was murder, then God the Father “murdered” Jesus because it was His will that He be sacrificed to save mankind. Likewise, Jesus committed suicide because He came to earth with the intent all along to be sacrificed.

Circumcision was another example of J’s sense of God giving arbitrary commands. What moral purpose does self mutilation serve?

It is a sign of the covenant, as the Bible says about 50 times. A foreskin is not exactly an essential part of the human body, and there were certain health risks related to it in those days. What is truly self-mutilation is a practice totally consistent with the contraceptive mentality: a vasectomy.

I also pointed to Gen 15 and the way Abraham discerns Yahweh’s will by cutting apart an animal and burning it. This text is written by a group of people who hold a very different theology of God than most Christians hold today.

This is directly related to the Mosaic Law: the same Law which Jesus said was in full effect in some sense, and which He came to fulfill (Matthew 5:17-19). It would also come as a great surprise to the author of Hebrews or to the Gospel writers who refer to the “Lamb of God” (see also the book of Revelation). Where do you think all that comes from? Where you see “very different” I simply see development. I am not approaching the Bible as an anthropologist, but as a Christian, who believes it to be inspired and entirely self-consistent.

Their God is arbitrary, and one acts with virtue not by acting rationally, but by obeying God’s every whim!

Sheer nonsense. What the Hebrews believed is shown in the book of Job and in books like Isaiah: God’s ways are higher than our ways, but He is not arbitrary or capricious: simply above our understanding (as we would expect of such a Being).

Two quick points: First, Pope John Paul II references the Yahwists and Elohists sources several times in Evangelium Vitae in his exegesis of the Cain and Abel story. Whether the theory is perfect or not, the use of this type of Biblical criticism has the papal stamp.

I am not absolutely against (some form of) the theory per se (let alone historical processes in compiling OT books); rather, I am primarily opposed to widespread uses of this theory which are arbitrary (as I explained) and which militate against a theory of unified inspiration (in other words, those which smack of theological liberalism and dissent).

Hermeneutics and belief in biblical inspiration and revelation are two different things. If the Bible as we know it is inspired in its entirety, then contradictions in theology cannot occur. I am presupposing development when I state this (bear in mind). But the whole thing is harmonious. That follows from the nature of the case: if it is “God-breathed,” it cannot be contradictory (at least in the original manuscripts: another discussion again).

You have actually said things like (paraphrasing): “I doubt that God told Abraham to kill Isaac.” That would entail a denial of inspiration and the trustworthiness of the biblical record (even involving New Testament espousal of these events). That leads you far afield from merely the Documentary Hypothesis.

Second, the goal of historical-critical methods is not to “explain away” what is inconvenient. Indeed, the methods often raise tougher questions for us. Rather, the goal of historical critical and literary methods of studying the Bible is truly and honestly trying to discern what the author of a particular passage intended.

I’m not opposed to intent of the author or a legitimate use of the historico-critical method, either (as I have already noted): only abuses of the same and the efforts of people who no longer hold to the high view of Holy Scripture, and who approach the study of the Bible like a butcher approaches a hog.

I have made my individual criticisms of your method. You would be mistaken to generalize those criticisms to all serious modern biblical scholarship. I am opposed to what I feel (as a Catholic) are departures from legitimate, tradition-affirming Bible scholarship, based on various hostile presuppositions brought to the work.

Furthermore, as a Catholic, I believe that there is more than one sense of Scripture (i.e. – the literal, the spiritual, the moral, the allegorical, and the anagogical, as well as the reading within tradition – see par 113-117 of the CCC).

So do I, which is why I possess and am rather fond of, Mark Shea’s book, Making Senses Out of Scripture, and I have noted this different hermeneutic in replying to Protestants.

However, as par 116 indicates, all meanings must be based in some way on the literal sense, which is the sense intended by the author derived through sound exegesis.

That’s right. I noted that in my paper above also.

Thus, I object to interpreting Gen 38 as though the same human author of Dt 25 were writing both passages, because the two pieces of literature have very different literary styles and theologies of God.

This illustrates the problem I have with your method (at least insofar as I am familiar with it, from this dialogue). So what if there are different literary styles!? This proves nothing in and of itself (though I agree that it might suggest a different author — just not necessarily, on these grounds alone).