This is a continuation of my response to I Don’t Have Enough Faith to Be an Atheist by Norm Geisler and Frank Turek. Though fifteen years old, this book continues to be a bestseller in the category of Christian apologetics. Part 1 of the critique is here.

Morality (Mother Teresa isn’t a good example)

Geisler and Turek (GT) spend 25 pages giving their argument for a divine source for morality. I’ve written a lot about the weak Christian justification for morality before (some of those posts are listed below), but this is the most thorough version of the Christian argument to which I’ve responded.

That doesn’t mean that it’s well thought out. The chapter is titled, “Mother Teresa vs. Hitler,” and we’re already off to a bad start. Mother Teresa isn’t the saint that GT imagine (well, okay, literally, she is). She has received much criticism. She was little concerned about healing her patients or even preventing their pain. She saw her patients’ suffering as a moral crucible and said, “There is something beautiful in seeing the poor accept their lot, to suffer it like Christ’s Passion. The world gains much from their suffering.” The goal of modern medicine is precisely the opposite—not to celebrate suffering and disease but to fight it.

GT’s moral arguments are shallow, and the same few mistakes are made repeatedly. I’ll give a fair amount of the argument rather than simplifying it, in the hope that this prepares you for similar arguments. Their argument is aimed at the choir. The thinking is confused and sloppy and at best is a pat on the head to assure Christians that they’ve backed the right horse.

The Moral Argument

At this point in the book, GT have given us their Cosmological and Teleological arguments. Their third is the Moral Law argument:

1. Every law has a law giver

2. There is a Moral Law

3. Therefore, there is a Moral Law Giver (page 171)

Newton’s Second Law of Motion (f = ma) is also a law. Must there be a physics law giver? GT will say yes, but we need evidence. With GT, we rarely go beyond an intuitive, kinda-feels-right type of argument, but I suppose that works well with their target audience.

One definition of objective morality . . .

The theme running through this argument is a Moral Law that mimics the Greek god Proteus, changing shape whenever we grab it. The Moral Law is a claim of objective morality, but “objective morality” is never clearly defined. Let’s start with William Lane Craig’s definition of objective morality: “moral values that are valid and binding whether anybody believes in them or not.”

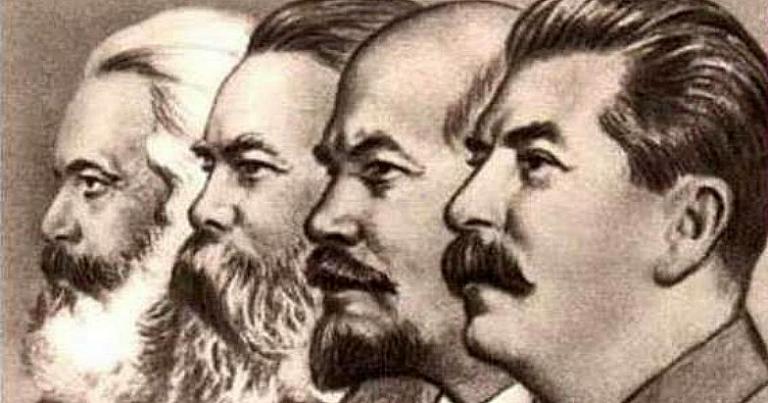

And let me define my opposing hypothesis, the natural morality position. Morality comes from two places. Our programming (from evolution) explains the traits that are largely common across all societies such as the Golden Rule. We’re all the same species, so it’s not surprising that we respond in similar ways to moral challenges. Our customs (from society) explain society-specific attitudes to issues like capital punishment, sex, blasphemy, honor, and so on. I will argue here that natural morality explains what we see better than GT’s Moral Law hypothesis.

More from GT:

Without an objective standard of meaning and morality, then life is meaningless and there’s nothing absolutely right or wrong. Everything is merely a matter of opinion. (171)

Bullshit. Look up “meaning” and “morality” in the dictionary, and you will find no mention of an objective standard. Our colloquial uses of meaning and morality work just fine in supporting a meaningful life. GT denigrate our human evaluation of morality as “merely” opinion, but I await evidence that Christians do things differently. It’s easy to appeal to an objective standard; the hard part is showing that that standard actually exists.

. . . but wait! There are more!

GT don’t feel obliged to stick with just one definition of objective morality.

When we say the Moral Law exists, we mean that all people are impressed with a fundamental sense of right and wrong. (171)

Redefinition! Now the Moral Law is that which we all feel. I suppose this is an appeal to our moral conscience? The focus is now on people, while William Lane Craig’s definition was on a morality grounded outside people.

Everyone knows there are absolute moral obligations. An absolute moral obligation is something that is binding on all people, at all times, in all places. And an absolute Moral Law implies an absolute Moral Law Giver. (171)

How about “slavery is wrong”? Is that binding on all people, at all times, in all places? I wonder why we didn’t get that from God and, indeed, got the opposite. Apparently in God’s youth, coveting needed prohibiting but not slavery.

Let me invent a term that will get some use as we go through this chapter: the Assumed Objectivity Fallacy. GT declares, “Everyone knows there are absolute moral obligations”? Wrong—the Assumed Objectivity Fallacy is either assuming without evidence that objective morals exist or assuming that everyone knows and accepts objective morality.

Back to GT:

This does not mean that every moral issue has easily recognizable answers. (171)

Redefinition! Now the Moral Law is something that we only dimly feel. The Moral Law is binding on all people . . . but we don’t really know for sure what the Moral Law is saying at every moral fork in the road. That seems unfair—to be bound by a law that we don’t understand—but I suppose GT’s god works in mysterious ways.

The challenge I like to give any believer in objective morality is to take some moral issue of the day—abortion, same-sex marriage, euthanasia, capital punishment—and give us a resolution of the issue that is (1) objectively correct and that (2) everyone can see is correct. Like GT, they justify neither the claim that it exists nor that this Moral Law is reliably accessible. I wonder then, what good is it?

GT’s childlike idea that our morality is objective isn’t supported by the dictionary or everyday experience. Being a grownup is apparently easier for some of us than others.

Continue with part 2.

Other posts responding to Christian views of morality:

- Explanation for Objective Morality? Another Fail.

- Morality’s Ruby Slippers

- Bad Atheist Arguments: “Morality Doesn’t Come From God”

- Frank Turek’s Criminally Bad C.R.I.M.E.S. Argument: Morality

- C. S. Lewis Gets Morality Wrong

they don’t have to worry about the answers.

— Thomas Pynchon

.

(This is an update of a post that originally appeared 9/17/15.)

Image from thierry ehrmann, CC license

.