Dr. Gavin Ortlund is a Reformed Baptist author, speaker, pastor, scholar, and apologist for the Christian faith. He has a Ph.D. from Fuller Theological Seminary in historical theology, and an M.Div from Covenant Theological Seminary. Gavin is the author of seven books as well as numerous academic and popular articles. For a list of publications, see his CV. He runs the very popular YouTube channel Truth Unites, which seeks to provide an “irenic” voice on theology, apologetics, and the Christian life. See also his website, Truth Unites and his blog.

In my opinion, he is currently the best and most influential popular-level Protestant apologist, who (especially) interacts with and offers thoughtful critiques of Catholic positions, from a refreshing ecumenical (not anti-Catholic) but nevertheless solidly Protestant perspective. That’s what I want to interact with, so I have done many replies to Gavin and will continue to do so. His words will be in blue.

*****

This is a response to one topic — and specifically, one sub-topic of it — in Gavin’s video, “Why Reformation Was Needed” (10-30-23). He introduces it as follows: “This video shows two areas reformation was needed in the late medieval Western church: (1) indulgences, and (2) persecution.” Since these are two completely different topics, I will concentrate on #2 in this reply, and then specifically, the medieval persecution of the radical Albigensian sect. In other replies, I’ll tackle further examples Gavin gives of Catholic persecution, and write about whether they were uniquely evil, or whether Protestants did similar things (in which case, I would ask why only Catholic sins and crimes are discussed, and not analogous Protestant ones?).

1:02 There were certain errors in the Church that had accrued and they needed to be corrected. That’s it. It’s as simple as that.

Except that Protestantism did not bring anything new in terms of religious freedom or tolerance. They didn’t correct that error of behavior. They persecuted just as fiercely, if not more so, than Catholics had. It was a general error of the age, which is why virtually everyone participated in it. There are many testimonies to this from non-Catholic writers. For example:

If any one still harbors the traditional prejudice that the early Protestants were more liberal, he must be undeceived. Save for a few splendid sayings of Luther, confined to the early years when he was powerless, there is hardly anything to be found among the leading reformers in favor of freedom of conscience. As soon as they had the power to persecute they did. (Preserved Smith, The Social Background of the Reformation, New York: Collier Books, 1962 [2nd part of author’s The Age of the Reformation, New York: 1920], 177)

The Reformers themselves . . . e.g., Luther, Beza, and especially Calvin, were as intolerant to dissentients as the Roman Catholic Church. (F. L. Cross & E. A. Livingstone, editors, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, 1983, 1383)

The principle which the Reformation had upheld in the youth of its rebellion — the right of private judgment — was as completely rejected by the Protestant leaders as by the Catholics . . . Toleration was now definitely less after the Reformation than before it. (Will Durant, The Reformation [volume 6 of 10-volume The Story of Civilization, 1967], New York: Simon & Schuster, 1957, 456; referring to the year 1555)

In time — especially after about 130 years of Catholic vs. Protestant religious wars (1518-1648), all sides figured out that religious persecution was wrong and a non-starter; so that virtually no one believes in it anymore. I argue that the entire issue is a wash (no one’s “hands are clean” in this) and ought not even be brought up. What I find objectionable is when Protestants try to imagine a fictitious, idealized, “scrubbed clean” past and argue that the early Protestants were — by nature — more tolerant of other viewpoints than Catholics were; that they were basically proponents of religious freedom over against Catholics.

In this video, Gavin makes this issue a central one in the Protestant Reformation. I am duty-bound as an apologist to provide “ther other side of the story” in order to counter the usual one-sided or greatly biased presentation of the topic. I have written a ton about these issues and I will try to bring some of the main points I have found, to bear.

This was actually one of the three major issues that persuaded me to become a Catholic (along with development of doctrine and contraception). Though I was never an anti-Catholic (I always thought Catholics were fellow Christians, as Gavin also does), I was a 100% gung-ho proponent of Protestantism and vigorous critic of the Inquisition (and infallibility), in possession of all the usual stereotypes of medieval Catholics, until in 1990 I started reading about the 16th century events and disputes from a Catholic perspective.

Yes, there actually is more than one point of view! This is the problem. Too often, both sides read only their own partisan viewpoints without reading the other side, too. It’s absolutely essential to let each side tell their own story and then to decide where the truth lies in particulars. When I did that, I saw that Catholics and Catholic history were very often — almost systematically — misrepresented and distorted, with corresponding and morally equivalent errors of historical Protestant teaching and behavior either ignored or greatly minimized.

I hasten to add that it works the other way, too. Underinformed or misinformed Catholics too often distort the nature of Protestant belief and behavior in the early days of that movement (as Gavin notes at the beginning of this video).

But given such a stacked deck, a Protestant will never even consider that Catholicism has been misrepresented, let alone being able to conceive of the possibility of becoming a Catholic. I couldn’t, myself, until I started to exercise the principle of fair play and read both sides. Because we live in an historically Protestant and now increasingly secular society in America (and secularism despises Catholicism much more than Protestantism), the tendency of anti-Catholicism tends to be far more prevalent than vice versa (whereas in traditionally Catholic countries the opposite sin would be the case, and I have often observed this).

2:11 It’s just as wrong to minimize scandals as it is to exaggerate them. And so we need to be historically accurate . . .

I completely agree. My point, again, is that both sides do this, but that the Protestant tendency to ignore the “skeletons” in its own closet is relatively much stronger in traditionally Protestant and secularizing cultures.

Gavin claims that he will be utilizing scholarly works without an overt Protestant bias, in detailing his claims of Catholic persecution. I know he will seek to do that, and that he is perfectly sincere, because I’ve observed his methodology (having replied to him about a dozen times). He’s blessedly free of any hint of the usual garden variety bigoted anti-Catholicism. But what I’ll be watching closely for, is to see if he also tackles Protestant intolerance. If not, then it’s too one-sided of a presentation, and needs a corrective such as I am providing now. A half-truth is not much better than a falsehood.

17:43 One of the objections . . . that I want to address right up front, is, “Protestants persecuted people too! That’s just how things were back in the medieval world.” . . . I . . . without any hesitation fault Protestants when they have sinned against those values [tolerance] as well. . . . Absolutely . . . I fault Protestants as well for historical persecutions and violence

This is very good and I greatly appreciate it. But we have to see how Gavin presents the history of religious persecutions and if he ignores how greatly Protestants were at fault. This will be examined in future replies of mine, because I only covered one big topic here. It seems to me that if there was little difference, that the notion that this was a major component of the Protestant Reformation is fundamentally in error. In other words, if both sides were doing the same thing, then it can hardly be said that Protestants corrected this error and made it a big plank of their intended reform of the larger Church. But Gavin indeed argues for Catholics supposedly being much much worse in this regard:

19:11 There is nothing comparable to the scale of late medieval violence. Some of the medieval Crusades classify as genocide. People don’t know this. [my italics and bolding]

He cited an historian (Mark Pegg), writing about the Albigensian crusade of the 13th century, who actually used the word “genocide” to describe it. The Albigensians and the related group, the Cathari, were extremely radical groups that were Manichaean or gnostic in belief: regarding matter as evil. See my article on the topic, from 1998. I cite five scholarly sources; four of them non-Catholics.

Dr. Pegg, however, takes the novel position that the Cathari and Albigensians didn’t exist. Okay, sure! Gavin mentioned his book,

[E]verything about the Cathars is utter fantasy, even down to their name. . . . more than a century of scholarship on both the Albigensian Crusade and heresy hasn’t been merely vaguely mistaken, or somewhat misguided, it has been breathtakingly wrong. (p. x)

It gets even worse. Pegg, as I suspected, after reading the above, seems to be an agnostic or atheist, and an anti-theist or anti-Christian, based on the following mocking, dismissive comments he made about the origins of these supposedly erroneous notions about a group of gnostic extremists that he thinks never existed at all. The error was largely caused, so he pontificates, by

equally mistaken notions about religion, which is narrowly defined by abiding doctrines, perennial philosophies, and timeless ideals. Scriptural consistency and theological cogency are what supposedly make religions . . . The fallacy behind it all is that pure principles form the core of every religion and that no matter how many civilizations rise and fall through the millennia, how many prophets come and go, the principles enduringly persist. Weightless, immaterial, untouched by historical contingency, they waft over centuries and societies like loose hot-air balloons. By combining these untethered beliefs, almost any history (secret or otherwise) can be strung together. (p. xi)

According to Pegg, the Cathari and Albigensians (or what we all pretend them to be) were “a very distinct Christian culture” which was falsely “accused of being heretical by the Catholic Church” (p. iv). Some strains of Protestant thought — most notably the “Landmark” Baptists — seek to incorporate the Albigensians and Cathari into a sort of non-Catholic “Protestant succession” through the centuries. They are gravely mistaken.

These groups believed that Jesus was a mere creature, who didn’t take on a body because all matter is evil. He wasn’t really born and He didn’t suffer the passion and crucifixion, and He didn’t rise again. Suicide was commendable, and the Cathari routinely starved themselves to death. Marriage and marital intercourse were unlawful, since they had to do with evil matter and reproduction. Satan, not God, created the visible world. They believed that every soul would be saved. All who died before the (illusory) passion of Jesus were damned.

Really great Christians, huh? Their supposed non-existence would come as a great shock to folks like M. D. Costen, author of The Cathars and the Albigensian Crusade (Manchester University Press, 1997). At Google Books, the page for this volume allows one to click on chapter 3, “The Cathars” and read some twenty pages about the historical origins of the group, which is thought to have historically derived from an earlier Manichean / dualist-type sect, the Bogomils of Bulgaria, which began in the mid-tenth century and “spread to many parts of the Byzantine Empire . . . Their doctrines sprang from a strain of Christian [?] thought which, although not orthodox, had very ancient roots in the early centuries of Christian belief and which had existed in the Balkans for many years” (p. 58).

Or we could mention The Albigensian Crusade (Faber & Faber, 2011), by renowned professor of history at Oxford, Jonathan Sumption. According to Dr. Pegg, this book, too, would essentially be a book of fiction, since he thinks the Cathari were “utter fantasy.” I need not cite any more of the many books on the topic.

Dr. Rebecca Rist, Associate Professor in Religious History at the University of Reading, critiqued this absurd questioning of the very existence of these groups, in her article, “Did the Cathars Exist?” (3-6-15):

In response to such interpretations which have provoked much debate – some of it very heated – many historians of heresy began to question if such revisionists had swung the pendulum too far back from the traditional reading of medieval polemical texts. . . .

In Heresy and Heretics in the Thirteenth Century: The Textual Representations (2013), Lucy Sackville provided a detailed history of the ‘revisionist’ historiography, and used the term ‘deconstruction’ to explain their methods, but also argued against the ‘revisionist’ idea that there was no cohesive intellectual Cathar theology. She pointed to the faulty logic of claiming that, although ‘revisionists’ rightly point to the Cathars’ opaque origins and their branding as ‘Manichaeans’ this means that we should disregard all evidence supporting their existence. Rather, she argued that, however the Cathars came into existence, there is plentiful evidence that by the thirteenth century their heresy had an organised, systematic and intellectually-based theology.

I would agree with these historians that, although medieval scholars, clergymen and theologians may have over emphasised their unity and coherence, and exaggerated the threat they posed to the Catholic Church, there is undoubted evidence for Cathars. I would also argue that there are serious flaws in the ‘revisionist’ or ‘de-constructionist’ argument. To claim that an organisation invented or constructed a heresy – in this instance that the Catholic Church ‘invented’ or ‘constructed’ the Cathar heresy – may arise if historians fail to take into account a procedure which medieval clergy widely used: namely to attack what the attacker (the Church) saw as the logical conclusion of the position attacked (a neatly packaged Cathar heresy) rather than necessarily what the attacked (the Cathars) actually said. Yet this does not mean that Cathars – those who espoused beliefs fundamentally at odds with Catholic Christianity – never existed. . . .

What shall we draw from such debates? I am inclined to the view that the ultimate origins of ‘Catharism’ do lie with the Manichaeans. Mani’s religion was the last and most successful of the great ancient semi-Christian dualisms. When one surveys the scholarship on Manichaeanism one realizes just what an enormous amount of the ancient known world, was – however briefly – Manichaean. Furthermore, the religion of Mani extended well beyond the ancient world as we know it – there were lots of Manichaeans as far as China – and for quite a long time. The detailed food prescriptions and the ‘perfecti’-‘credentes’ distinction also appear just too close to Manichaean practices to be coincidental: for Mani the ‘credentes’ were called ‘audientes’ – among whom St Augustine of Hippo counted himself when he belonged to the sect. So it does seem quite possible that the dualism in ‘Catharism’ derived ultimately from this source, though how it reached the Cathars – or rather in the first instance the Bogomils – remains uncertain. Even more scholarship is needed in this area.

One estimate of the number of deaths involved is from Colin Martin Tatz and Winton Higgins, in their book, The Magnitude of Genocide (ABC-CLIO, 2016) They think it was at least 200,000 (p. 214). Of course I don’t agree at all with wiping these gnostic sectarians out, as was done in many cities or areas (not even a single one; I am opposed to capital punishment). But this was the belief at the time: heresy was more dangerous than even murder, because it could cause people to be damned and go to hell; therefore, it ought to be persecuted at least as much as murderers are.

That was the reasoning behind much — if not most — persecution, from all sides. It was actually a concern for the well-being of society and for souls (a thing few seem to even consider when condemning it). It usually — wrong as I think it was — had a good motivation, at least in theory, and a spiritual rationale beyond merely bloodthirstiness or power plays, even though virtually all Christians reject the thinking today and oppose coercion.

The Catholic Encyclopedia (1913) stated (“Albigensees”): “Albigensianism was not a Christian heresy but an extra-Christian religion . . . What the Church combated was principles that led directly not only to the ruin of Christianity, but to the very extinction of the human race.” It stated about early attempts by the Church to deal with this belief-system:

Its condemnation by the Council of Toulouse (1119) did not prevent the evil from spreading. Pope Eugene III (1145-53) sent a legate, Cardinal Alberic of Ostia, to Languedoc (1145), and St. Bernard seconded the legate’s efforts. But their preaching produced no lasting effect. The Council of Reims (1148) excommunicated the protectors “of the heretics of Gascony and Provence.” That of Tours (1163) decreed that the Albigenses should be imprisoned and their property confiscated. A religious disputation was held (1165) at Lombez, with the usual unsatisfactory result of such conferences. Two years later, the Albigenses held a general council at Toulouse, their chief centre of activity. The Cardinal-Legate Peter made another attempt at peaceful settlement (1178), but he was received with derision.

Note that almost sixty years of attempted talks and reasonable discussion took place. That’s a long time! Eventually, all of that broke down and the recourse was to force. The article above describes the historically complex progression. Once again, I do not condone any of that (I’m as much a proponent of religious freedom as Gavin), but in context it can be understood at least to some extent, if not ever justified. However the Church reacted, this was truly a threat to the entire society and Christianity itself. By 1207 it had infected over 1000 cities or towns. And so the Christians felt that they had to act.

Was it terrible? Yes. I totally agree with Gavin. Is is defensible? No; and I don’t defend it. But I try to understand it in its historical context. And is this sort of thing only Catholic? No; assuredly not! Gavin talks about the “scale” being much greater than (implied) anything similar in Protestantism. I’m not sure about that, myself, at all. I have written three in-depth articles (one [17,800 words] / two / three) about the Peasants’ Revolt in Germany in 1524-1525.

Like all such events, it’s very complex and not at all given to quick summary. A convincing argument can be made, however, that Martin Luther was a large contributing cause — perhaps the largest one — to stirring up the peasants (and also a big factor in calling for their later suppression). I wrote in my long paper about this in 2003 (that had tons of citations from historians of all sides):

Historians on both sides are in agreement that Luther never supported the Peasants’ Revolt (or insurrection in general). Many, however (including Roland Bainton, the famous Protestant author of the biography Here I Stand), believe that he used highly intemperate language that couldn’t help but be misinterpreted in the worst possible sense by the peasants. I agree with these Protestant scholars, . . .

No Catholic (or Protestant) historian I have found — not even Janssen — asserts that Luther deliberately wanted to cause the Peasants’ Revolt, or that he was the primary cause of it. Quite the contrary . . .

The relationship between this divine wrath and judgment and those whom God uses to execute it, however, remains somewhat obscure, unclear, and ambiguous in Luther’s writings. Perhaps the key to this conundrum is found in a remarkable statement he made in a private letter, dated 4 May 1525: “If God permits the peasants to extirpate the princes to fulfil his wrath, he will give them hell fire for it as a reward.”

So, while Luther opposed insurrection on principle, there is a tension in his seemingly contradictory utterances between opposition to the populace taking up arms against spiritual and political tyranny, and a deluded confidence and at times almost gleeful wish that apocalyptic judgment was soon to occur, regardless of the means God used to bring it about (one recalls the ancient Babylonians, whom God used to judge the Hebrews). This produces an odd combination of sincere disclaimers against advocating violence, accompanied by (often in the same piece of writing) thinly-veiled quasi-threats and quasi-prophetic judgments upon the powers of the time, sternly warning of the impending Apocalypse and destruction of the “Romish Sodom” and all its pomps, pretenses, corruptions, and vices.

Luther wrote, for example, to the German princes in early May 1525:

For you ought to know, dear lords, that God is doing this because this raging of yours cannot and will not and ought not be endured for long. You must become different men and yield to God’s Word. If you do not do this amicably and willingly, then you will be compelled to it by force and destruction. If these peasants do not do it for you, others will . . . It is not the peasants, dear lords, who are resisting you; it is God Himself . . . (An Admonition to Peace: A Reply to the Twelve Articles of the Peasants in Swabia, Philadelphia edition of Luther’s works [“PE”], 1930, IV, 219-244, translated by C.M. Jacobs; citations from 220-227, 230-233, 240-244; WA, XVIII, 292 ff.; EA, XXIV, 259 ff.)

But then when the whole thing got way out of hand, Luther famously advocated the slaughter of the very civilians whom he arguably had emboldened to make the uprising. Within only about two weeks after he had written the above, he wrote:

[I]if a man is an open rebel every man is his judge and executioner, just as when a fire starts, the first to put it out is the best man. For rebellion is not simple murder, but is like a great fire, which attacks and lays waste a whole land. Thus rebellion brings with it a land full of murder and bloodshed, makes widows and orphans, and turns everything upside down, like the greatest disaster. Therefore let everyone who can, smite, slay, and stab, secretly or openly, remembering that nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful, or devilish than a rebel. It is just as when one must kill a mad dog; if you do not strike him, he will strike you, and a whole land with you. (Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants, PE, IV, 248-254, translated by C.M. Jacobs; citations from 248-251, 254; WA, XVIII, 357-361; EA, XXIV, 288-294)

How is that all that different (in terms of wrongness) from the suppression of the Albigensians? I don’t see much difference, excepting perhaps that the peasants were more violent and were committing acts of insurrection. But if one is at the edge of a sword, about to be killed (and most victims were inadequately armed farmers), such differences matter very little. Note that he was advocating that “everyone who can” should kill these rebels, not just the appropriate civil or military authorities.

The usual figure given for deaths in the Peasants’ Revolt is 100,000. Peter Blickle, in his 1981 book, The Revolution of 1525: The German Peasants War from a New Perspective (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981, p. 165), confirms this figure.

Secondly, Luther and Melanchthon advocated the execution of Anabaptists — even the completely peaceful ones — according to exactly the same rationale: intolerable sedition and consequences for society if nothing is done (which is similar to why the Albigensians were killed). I’ve written about this, too. Protestant church historian Roland Bainton, author of the most famous and influential biography of Luther in English, Here I Stand (1950), which I read in 1984 when Luther was a big hero of mine, wrote in his book, Studies on the Reformation (Boston: Beacon Press, 1963):

The reformers can be ranged on the side of liberty only if the younger Luther be pitted against the older or the left wing of the Reformation against the right . . .

By the beginning of March 1530 Luther gave his consent to the death penalty for Anabaptists, but on the ground that they were not only blasphemers, but highly seditious. . . .

Any doors which Luther might have left open in the second period from 1525 to 1530 were closed by Melanchthon in the memorandum of 1531. Rejection of the ministerial office was described as insufferable blasphemy, and destruction of the Church was considered sedition against the ecclesiastical order, punishable like other sedition. Luther added his assent,

for though it seems cruel to punish them with the sword, it is more cruel that they damn the ministry of the Word, have no certain teaching, and suppress the true, and thus upset society. [CR, IV, 739-740 (1531). Wappler, Inquisition, 61-62; Paulus, 41-43]

The second memorandum composed by Melanchthon and signed by Luther in 1536 is of extreme importance in making clear what was involved. The circumstance was that Philip of Hesse who steadfastly refused to go beyond banishment and imprisonment in matters of faith, invited the theologians in a number of localities to give him advice. One of the most severe among the replies was that which came from Wittenberg. In this document the Anabaptists were declared to be seditious and blasphemous, but in what did their sedition consist? The answer was: not by reason of armed revolution, but on the contrary, by reason of pacifism.

They teach that a Christian should not use a sword, should not serve as a magistrate, should not swear or hold property, may desert an unbelieving wife. These articles are seditions and the holders of them may be punished with the sword. We must pay no attention to their avowal ‘we did no one any harm’, because if they persuaded everybody there would be no government. If it be objected that the magistrate should not compel anyone to the faith the answer is that he punishes no one for his opinions in his heart, but only on account of the outward word and teaching. [Melanchthon]

The memorandum goes on to say that there were other tenets of the Anabaptists touching upon spiritual matters such as their teaching about infant baptism, original sin and illumination apart from God’s Word.

What now would happen if children were not baptized, if not that our whole society would become openly heathen? If then one holds only the articles in spiritual matters on infant baptism and original sin and unnecessary separation, because these articles are important, because it is a serious matter to cast children out of Christendom and to have two sets of people, the one baptized and the other unbaptized, because then the Anabaptists have some dreadful articles, we judge that in this case also the obstinate are to be put to death. [WA, L, 12] [Melanchthon]

Luther signed.

This document makes it perfectly plain that the Anabaptists were revolutionary, not in the sense of physical violence, but in the sense that their program entailed a complete reorientation of Church, state and society. For this they were to be put to death.

See also: Luther’s Attitudes on Religious Liberty [Roland H. Bainton] [2-16-06])

John Calvin got in on the act, too (he didn’t just go after Michael Servetus), on the same basis:

Moses . . . now subjoins the punishment of such as should creep in under the name of a prophet to draw away the people into rebellion. For he does not condemn to capital punishment those who may have spread false doctrine, only on account of some particular or trifling error, but those who are the authors of apostasy, and so who pluck up religion by the roots. . . .

[I]n a well constituted polity, profane men are by no means to be tolerated, by whom religion is subverted. . . . God commands the false prophets to be put to death, who pluck up the foundations of religion, and are the authors and leaders of rebellion. . . .

God might, indeed, do without the assistance of the sword in defending religion; but such is not His will. And what wonder if God should command magistrates to be the avengers of His glory, when He neither wills nor suffers that thefts, fornications, and drunkenness should be exempt from punishment. In minor offenses it shall not be lawful for the judge to hesitate; and when the worship of God and the whole of religion is violated, shall so great a crime be fostered by his dissimulation? Capital punishment shall be decreed against adulterers; but shall the despisers of God be permitted with impunity to adulterate the doctrines of salvation, and to draw away wretched souls from the faith? . . .

Christ, indeed as He is meek, would also, I confess, have us to be imitators of His gentleness, but that does not prevent pious magistrates from providing for the tranquillity and safety of the Church by their defense of godliness; since to neglect this part of their duty, would be the greatest perfidy and cruelty. And assuredly nothing can be more base than, when we see wretched souls drawn away to eternal destruction by reason of the impunity conceded to impious, wicked, and perverse impostors, to count the salvation of those souls for nothing. (Harmony of the Law, Vol. 2, Commentary on Deuteronomy 13:5; written in 1563)

I bring this up mainly to illustrate the chilling principle or rationale involved (accusations of sedition, treason, and unacceptable subversion of society), which was less justified in their case than it was for the Albigensians, who were not Christians at all. Gavin (or myself in my Protestant days, when I came to believe in adult believer’s baptism, and got “baptized” in 1982 at age 24) could have been executed for believing in adult baptism, according to Luther and his friend and successor Melanchthon. That was considered subversive of good German Lutheran Christian society and seditious. At one point Melanchthon even advocated execution for disbelief in the real presence in the Eucharist, before he himself stopped believing in it.

Catholics were in on this persecution, too. But remember, Gavin is claiming that the Protestant Reformation was all about stopping religious persecution and intolerance. Protestants were supposedly so much better than Catholics on this score. It simply isn’t true. How many Anabaptists were executed for their beliefs? It’s hard to say. But the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online takes a shot (“Martyrs” / “The Number of Anabaptist Martyrs”):

Documentary evidence has been preserved only in part, some of it probably intentionally destroyed. In the “Anabaptist hunts” in the territory of the Swabian League and in the Netherlands as well as in other regions where regular trials were dispensed with, there was most likely no record of even the names or number of victims. Nevertheless an attempt has been made to determine the number from oral and written sources. For the Netherlands, Samuel Cramer has conservatively set the number at 1,500 (DB 1902, 150 ff.). He based this figure on the fairly complete records of Antwerp and Ghent, estimating the number in the other provinces on this basis, which should yield a sufficiently reliable result. W. J. Kühler also surmised that the number of martyrs was at least 1,500 (Geschiedenis I, 270) ; N. van der Zijpp (Geschiedenis, 77) is of the opinion that the number of martyrs in Belgium and in the Netherlands should be estimated as at least 2,500, on the basis of his studies on Mennonite martyrdom in the Netherlands. The best collection of data on the fate and testimonies of the martyrs is found in the Martyrs’ Mirror by Tieleman J. van Braght, who lists about 800 Anabaptist martyrs by name. A larger number is given in summary form, because data and names were lacking.

For South Germany the list in the Hutterite Geschicht-Buch is of particular importance. According to the list given in Beck (pp. 278 ff.) the number of martyrs up to the year 1581 was 2,169. But the numbers given for the individual districts do not agree with this figure, totaling only 1,396. It is not clear how this difference is to be explained. (For Tyrol the list of 1581 gives the number as 338, whereas a government declaration of Nov. 11, 1539, set the number of Anabaptists executed at over 600. —Hege.) Wolkan presents a list that deviates in some instances from the above, and gives a total of 1,580 martyrs by 1542. Beck has on page 310 an additional list that was found on Julius Lober in 1531, listing 390 martyrs.

None of these lists can claim to be exhaustive; in Beck all the executions recorded in the court records in Switzerland, and in Wolkan some of them, are lacking, nor can they offer absolute reliability, since they are sometimes based on oral information, as in the case of the 350 in Alzey (see Palatinate) and the 600 who were said by Sebastian Franck to have been executed at Ensisheim. Nevertheless the total must not be underestimated, and would probably exceed rather than fall below 4,000. (cf. entries for Martin Luther, Philipp Melanchthon, and Saxony; the latter details many specific examples of persecution and execution of Anabaptists, right in Luther’s territory)

Zwingli, another major early Protestant leader, seems to have concurred as well. The above encyclopedia in its article on him, stated:

Zwingli’s personal attitude toward the increasingly repressive police measures taken by the authorities (prison February 1525; money fines and torture late 1525; death penalty and banishment decreed in 1526 and applied in 1527) has not been adequately studied. On the one hand he seems to have urged moderation and to have intervened personally in favor of some prisoners, yet at the same time he is reported to have preached that repression is the duty of a legitimate government; and in view of his dominant role in Zürich’s public life one can hardly conceive of these measures being taken against his will or without his approval.

As a third example, I would submit the massive mania of the witch hunts, which was also a joint Catholic-Protestant phenomenon. The Catholic Inquisition itself, it should be noted, was not — by and large — concerned with the question of witches per se. English historian Dominic Selwood, wrote in his article, “How Protestantism fuelled Europe’s deadly witch craze” (The Telegraph, 16 March 2016):

The Gregorian Inquisition had been established to deal with the religious matter of heresy, not the secular issue of witchcraft. Pope Alexander IV spelled this out clearly in a 1258 canon which forbade inquisitions into sorcery unless there was also manifest heresy. And this view was even confirmed and acknowledged by the infamous inquisitor Bernard Gui (immortalised by Umberto Eco in The Name of the Rose), who wrote in his influential inquisitors’ manual that, by itself, sorcery did not come within the Inquisition’s jurisdiction. In sum, the Church did not want the Inquisition sucked into witch trials, which were for the secular courts. . . .

The period of the European witch trials with the most active phase and the largest number of fatalities seems to have been between 1560 and 1630, according to Robert W. Thurston, Witch, Wicce, Mother Goose: The Rise and Fall of the Witch Hunts in Europe and North America (Edinburgh: Longman, 2001, p. 79). The period between 1560 and 1670 saw more than 40,000 deaths, according to James Carroll’s book, Jerusalem, Jerusalem: How the Ancient City Ignited Our Modern World (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011, p. 166). Other historians estimate that as many as 60,000 reputed “witches” were executed.

See heavily documented Wikipedia articles about witch hunts in various Protestant countries: Denmark (> 500), England (> 500), Finland (> 277), Iceland, Latvia, Estonia, Netherlands (~ 200), Norway (277-350), Scotland (> 1500), and Sweden. By contrast, Catholic Spain had “few [executions for witchcraft] in comparison with most of Europe.” And the witch trials in Portugal were “perhaps the fewest in all of Europe.” Some Catholic countries were much worse, and some Protestant countries were really bad. Others of both faiths did a lot better. This is another reason why a “Catholic vs. Protestant” approach isn’t the relevant or correct way to analyze the phenomenon, and it shows once again that these sorts of travesties occurred on both sides.

A fourth obvious example is the abominable persecution of Catholics in England. Catholics had no power at all, except during the reign of Mary Tudor, aka “Bloody Mary”, from 1553-1558. She executed 283 Protestants from 1555-1558, mostly by burning, according to Eamon Duffy, Fires of Faith: Catholic England Under Mary Tudor (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009, p. 79).

But apart from those five years, Catholicism essentially became illegal, and being a Catholic priest or harboring one was a capital offense, from the time of Butcher Henry VIII all the way till 1829 (in terms of the abolition of all anti-Catholic penal laws). It was the same rationale, again, that Luther had used just a few years earlier: not acknowledging Henry VIII as the head of the English church, rather than the pope, was not only “heresy” but also supposedly the worst sort of treason and sedition; thus worthy of death.

And so there were many executions, in which people were hanged (but not till death), disemboweled, had their hearts removed while they were alive, and then their legs and arms and heads cut off. Very civilized stuff! And remember, this was all done to those whom Gavin considers fellow Christians: for the “crime” of being Catholics, whereas Catholics in earlier times killed Albigensians, who were not Christians at all. I documented the bloodthirsty Anglican persecution of Catholics in several papers:

430 Catholic Martyrs Murdered by Henry VIII (1534-1544) [2-6-08]

312 Catholic Martyrs & Confessors Under “Good Queen Bess” (Queen Elizabeth: r. 1558-1603) [2-8-08]

189 English Catholic Martyrs & Heroic Confessors: 1603-1729 [2-16-08]

444 Irish Catholic Martyrs and Heroic Confessors: 1565-1713 [2-27-08]

[at least 1375 documented Catholic martyrs in the British Isles]

In conclusion, mass killings, or “genocide” (?) based on heretical beliefs or harmfully “seditious / treasonous” (including peaceful) ones were not solely a Catholic phenomenon, and neither side can claim a triumphant moral superiority. That being the case, why bring this up at all in the context of comparative dialogues regarding Catholicism and Protestantism and “Reformation Day”?

Both sides used to do it, and both eventually stopped doing it, recognizing that it is wrong and goes too far. It’s a wash, and in my opinion, it ought not be discussed in these contexts. I only do because of the consistently one-sided presentation of these matters. I’m responding to that. Otherwise, I wouldn’t write about any of this (except if an atheist brought it up as a reason to reject Catholicism or larger Christianity. I have to balance the score, for the sake of historical fairness and objectivity. As an educator I can do no less in good conscience. My approach in those instances is “let folks read both sides of disputed issues and make up their own minds.”

**

See my follow-up article: Reply To Gavin Ortlund: Catholic Inquisitions; Hus [2-7-24]

***

*

Practical Matters: Perhaps some of my 4,500+ free online articles (the most comprehensive “one-stop” Catholic apologetics site) or fifty-five books have helped you (by God’s grace) to decide to become Catholic or to return to the Church, or better understand some doctrines and why we believe them.

Or you may believe my work is worthy to support for the purpose of apologetics and evangelism in general. If so, please seriously consider a much-needed financial contribution. I’m always in need of more funds: especially monthly support. “The laborer is worthy of his wages” (1 Tim 5:18, NKJV). 1 December 2021 was my 20th anniversary as a full-time Catholic apologist, and February 2022 marked the 25th anniversary of my blog.

PayPal donations are the easiest: just send to my email address: [email protected]. Here’s also a second page to get to PayPal. You’ll see the term “Catholic Used Book Service”, which is my old side-business. To learn about the different methods of contributing (including Zelle), see my page: About Catholic Apologist Dave Armstrong / Donation Information. Thanks a million from the bottom of my heart!

*

***

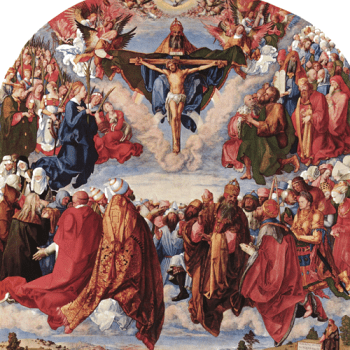

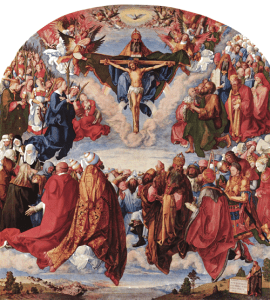

Photo credit: St. Dominic de Guzman and the Albigensians (1493-1499), by Pedro Berruguete (1450–1504). This portrays the story of a dispute between Saint Dominic and the Cathars in which the books of both were thrown on a fire and St. Dominic’s books were miraculously preserved from the flames. [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

Summary: Gavin Ortlund argued in a video that one of two big reasons for the Protestant Reformation was Catholic persecution. But the latter was no better among Protestants.