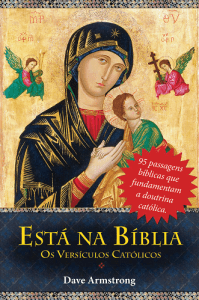

[see book and purchase information]

Francisco Tourinho is a Brazilian Calvinist apologist. He described his theological credentials on my Facebook page:

I have the respect of the academic community for my articles published in peer review magazines, translation of unpublished classical works into Portuguese and also the production of a book in the year 2019 with more than 2000 copies sold (with no marketing). In addition I have higher education in physical education from Piauí State University and theology from the Assemblies of God Biblical Institute, am currently working towards a Masters from Covenant Baptist Theological Seminary, and did post-graduate work at Dom Bosco Catholic University. Also, I am a professor in the Reformed Scholasticism discipline at the Jonathan Edwards Seminary in the postgraduate course in Philosophical Theology. [edited slightly for more flowing English]

My previous replies:

Justification: A Catholic Perspective (vs. Francisco Tourinho) [6-22-22]

Reply to Francisco Tourinho on Justification: Round 2 (Pt. 1) [+ Part 2] [+ Part 3] [7-19-22]

This is an ongoing debate, which we plan to make into a book, both in Portugese and English. Francisco’s words will be in blue. Mine from my previous installment will be in green. I will try very hard to cite my own past words less, for two reasons: 1) the sake of relative brevity, and 2) because the back-and-forth will be preserved in a more convenient and accessible way in the book (probably with some sort of handy numerical and index system).

In instances where I agree with Francisco, there is no reason to repeat his words again, either. I’ll be responding to Francisco’s current argument and noting if and when he misunderstood or overlooked something I think is important: in which case I’ll sometimes have to cite my past words. I use RSV for all Bible passages (both mine and Francisco’s) unless otherwise indicated.

His current reply is entitled, Justificação pela fé: perspectiva protestante (contra Armstrong): Rodada 3. Parte 1. [Justification by Faith: Protestant Perspective (Contra Armstrong): Round 3. Part 1] (10-12-22). Note that he is replying only to Part I of my previous Round 2 reply. When he writes his replies to my Parts II and III and I counter-reply, the debate will be completed, by mutual agreement, except for brief closing statements. I get the (rather large) advantage of “having the last word” because Francisco chose the topic and wrote the first installment.

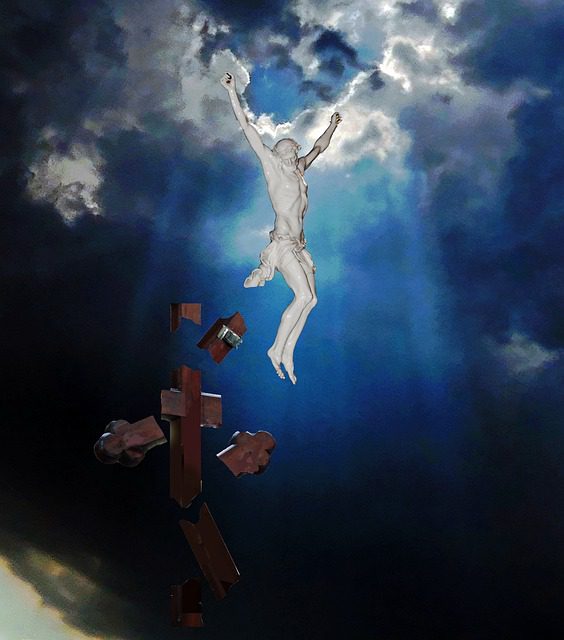

I would like the reader to pay attention to the fulcrum of my argument. Any reader is “authorized” to overlook any detail except this one: the perfect work of Jesus Christ on Calvary’s cross!

Yes, of course it’s perfect because we’re talking about God.

The foundation of Sola Fide (justification by faith alone) is the perfect work of Jesus on the cross. For only by faith can we receive Jesus Christ, and in receiving Jesus, we also receive his merits and his righteousness. How then are we not already perfectly justified the moment we receive it?

We are in initial justification, but then a process is involved whereby we continually appropriate the perfect work of Jesus on the cross. I have already demonstrated this with much Scripture.

A process of justification in which works also justify when accompanied by faith denies the perfection of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, as it would have as a logical consequence the teaching that Christ is not enough, since my works must conquer something that Christ did not give me. Only by his death. Jesus Christ, the Just, transfers his righteousness to us, while taking our sin upon himself. Read the text with this in mind, for I will repeat this point several times, not for the absence of others, but for its gigantic importance.

It’s fine to repeat an emphasis, as long as readers bear in mind that mere repetition adds nothing substantive to an existing argument. St. Paul is the one who clearly teaches some sort of process involved in justification and salvation. Yes, the work of Christ on the cross is perfect and sufficient for any person who accepts the grace to be saved. But the acceptance and application of it to persons (especially in Pauline theology) is not instant, and requires our vigilant effort:

Romans 8:17 (RSV) and if children, then heirs, heirs of God and fellow heirs with Christ, provided we suffer with him in order that we may also be glorified with him.

1 Corinthians 9:27 but I pommel my body and subdue it, lest after preaching to others I myself should be disqualified.

1 Corinthians 10:12 Therefore let any one who thinks that he stands take heed lest he fall.

Philippians 3:11-14 that if possible I may attain the resurrection from the dead. Not that I have already obtained this or am already perfect; but I press on to make it my own, because Christ Jesus has made me his own. Brethren, I do not consider that I have made it my own . . . I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus.

Colossians 1:22-24 he has now reconciled in his body of flesh by his death, in order to present you holy and blameless and irreproachable before him, [23] provided that you continue in the faith, stable and steadfast, not shifting from the hope of the gospel which you heard, which has been preached to every creature under heaven, and of which I, Paul, became a minister. [24] Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I complete what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church,

Hebrews 3:14 For we share in Christ, if only we hold our first confidence firm to the end.

Hebrews 10:39 But we are not of those who shrink back and are destroyed, but of those who have faith and keep their souls.

Revelation 2:10 Be faithful unto death, and I will give you the crown of life.

If I have mentioned some of these before, they can be omitted in the book version. At this point, it’s too tedious to go back and check.

Contrary to what I have defined, Mr. Armstrong does not make a practical – or even theoretical – difference between justification and sanctification, although at times he claims to be different things, using the terms interchangeably in his exegesis of Biblical texts. As we will see later, he fails to demonstrate the difference between one and the other.

They are organically connected; two sides of the same coin: just as faith and works and Bible and tradition are. But distinctions can be made (I agree). In fact, I offered a meticulous definition of both in my previous reply (search “I’m glad to do so” to find it). I cited my first book, which is semi-catechetical; massively citing the Catechism of the Catholic Church and Trent. Here are brief definitions from that treatment, citing my own words in my book:

Justification . . . is a true eradication of sin, a supernatural infusion of grace, and a renewal of the inner man. [derived from: CCC #1987-1992; Trent, Decree on Justification, chapters 7-8]

Sanctification is the process of being made actually holy, not merely legally declared so. [CCC, #1987, 1990, 2000]

I fleshed it out much further. I fail to see how this is insufficient for our task of debating the definitions and concepts, or how I could be any clearer than I was.

I made it clear last time what the practical effect was when I said in my previous article: if justification is a forensic statement in which the merits of Christ are all imputed to me through faith, then I can have peace with God, as St. in Romans 5:1: “Justified through faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Christ Jesus.” If Christ fulfilled the Law and also had perfect obedience, then his merits are perfect when imputed to me and I can therefore have peace with God – the just for the unjust. This peace will not be obtained if justification is a lifelong process, not without great difficulty.

This is mere repetition, thus adding nothing to the debate. I already addressed it, and I did again, above, with eight biblical passages. That’s my “problem.” I can’t figure out a way to ignore and dismiss so many scriptural passages that expressly contradict Protestant soteriology.

When will I be righteous before God if my justification also depends on my good works? How many good works will I have to do to be considered righteous before God?

We don’t need to know that. All we need to know and do is to “press on toward the goal” and “continue in the faith, stable and steadfast”: as the Apostle Paul did (Phil 3:14 and Col 3:23), because justification is not yet “obtained” (Phil 3:12). We have to “keep our eyes on Jesus”: as we used to say as evangelicals. And we have to do this “lest” we “should be disqualified” (1 Cor 9:27). We also have to “suffer with” Jesus in order to be God’s “children” and “heirs of God” (Rom 8:17).

Paul — as always — is very straightforward, matter-of-fact, and blunt about all this (one of the million things I love about him). None of this suggests (to put it mildly) instant, irrevocable justification.

Although faith is not against works, they are exclusive with regard to the causes of justification, sanctification and salvation before God, for Saint Paul says: “For by grace you have been saved through faith, and that not of yourselves. , it is the gift of God; does not come through works, so that no one may boast on this account.” Eph 2.8,9

This is referring to initial justification, as I believe (without looking!), as indicated in context by 2:5 (“we were dead through our trespasses”), that I have noted before in this debate. The very next verse (which Protestants habitually omit) shows the organic connection:

Ephesians 2:10 For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them.

I had a dear late devout Baptist (and Marxist!) friend, who always would point out how Protestants leave out Ephesians 2:10. It doesn’t explicitly state here that these works are indirectly tied to salvation, in conjunction with grace and faith, but that idea occurs elsewhere, many times, as I have already shown.

Good works are not formal causes of salvation at any time, but only manifestations of the transformation that God makes in us, for the working follows the Being. Therefore even holy works must be the fruits of holiness, not the cause of it. To say that works are the cause of salvation, therefore, of holiness, is Pelagianism, since every good work of supernatural value presupposes grace, and the action of grace presupposes an enablement, therefore, a sanctification. Mr. Armstrong seems to forget this Biblical and metaphysical principle: the good fruit is the effect of the good tree and not the other way around; on the other hand, we know the good tree by its fruits.

The Bible teaches us (fifty times!) that works play a key role in whether one is saved and allowed to enter heaven or not. I’ve already gone through that reasoning in depth. What is most striking about the fifty passage is that faith alone is never mentioned as the cause for salvation. “Faith” by itself is mentioned but once: in Revelation 21:8, which includes the “faithless” among those who will be damned for eternity. Even there it is surrounded by many bad works that characterize the reprobate person. If Jesus had attended a good Protestant seminary and gotten up to speed on His soteriology, Matthew 25 would have read quite differently; something like the following:

Then I saw a great white throne and Him who sat upon it, from whose presence earth and heaven fled away, and no place was found for them. And I saw the dead, the great and the small, standing before the throne, and books were opened; and another book was opened, which is the book of life; and the dead were judged from the things which were written in the books, according to whether they had Faith Alone. And the sea gave up the dead which were in it, and death and Hades gave up the dead which were in them; and they were judged, every one of them according to whether they had Faith Alone.

Instead, we hear from our Lord Jesus all this useless talk about works, as if they had anything to do with salvation! Doesn’t Jesus know that works have no connection to salvation whatsoever, and that sanctification and justification are entirely separated in good, orthodox evangelical or Calvinist theology? Maybe our Lord Jesus attended a liberal synagogue. Why does Jesus keep talking about feeding the hungry, giving water to the thirsty, inviting in strangers, clothing the naked, visiting prisoners, and being judged “according to their deeds”? What in the world do all these “works” have to do with salvation? Why doesn’t Jesus talk about Faith Alone??!! Something is seriously wrong here.

We have a serious problem here, for from the beginning I accuse the theology of Rome of equating justification and sanctification.

We make a sharp differentiation between initial and subsequent justification; and at least some distinction between sanctification and justification.

Mr. Armstrong denies, according to his statements, that justification is the same as sanctification, but maintains that the two are so intertwined that one cannot exist without the other, something with which I need not disagree at all.

Good!

Nevertheless, I maintain that the issue is not exactly this, but that we do not see the difference between one and the other in their definitions or in their practical applications. When he says that justification is “a true eradication of sin . . . and a renewal of the inward man,” the concept used here does not differ from sanctification.

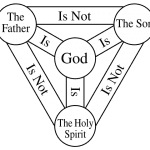

Yes, precisely because we believe in infused and intrinsic justification, whereas Protestants believe only in declarative, imparted, and extrinsic justification. Baptist theologian Augustus Strong explains Protestant justification very well:

. . . a declarative act, as distinguished from an efficient act; an act of God external to the sinner, as distinguished from an act within the sinner’s nature and changing that nature; a judicial act, as distinguished from a sovereign act; an act based upon and logically presupposing the sinner’s union with Christ, as distinguished from an act which causes and is followed by that union with Christ. (Systematic Theology, Westwood, New Jersey: Fleming H. Revell, 1967; originally 1907, 849)

So does Presbyterian theologian Charles Hodge:

It does not produce any subjective change in the person justified. It does not effect a change of character, making those good who were bad, those holy who were unholy. That is done in regeneration and sanctification . . . It is a forensic or judicial act . . . It is a declarative act in which God pronounces the sinner just or righteous . . . (Systematic Theology, abridged one-volume edition by Edward N. Gross, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1988; originally 1873, 3 volumes; 454)

But Catholics believe that justification actually does something in souls, based on the Bible:

Romans 5:19 For as by one man’s disobedience many were made sinners, so by one man’s obedience many will be made righteous.

1 Corinthians 6:11 But you were washed, you were sanctified, you were justified in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ and in the Spirit of our God.

2 Corinthians 5:17 Therefore, if any one is in Christ, he is a new creation; the old has passed away, behold, the new has come. (cf. Gal 6:15)

Titus 2:14 Who gave himself for us, that he might redeem us from all iniquity, and purify unto himself a peculiar people, zealous of good works.

Titus 3:5-7 he saved us, not because of deeds done by us in righteousness, but in virtue of his own mercy, by the washing of regeneration and renewal in the Holy Spirit, [6] which he poured out upon us richly through Jesus Christ our Savior, [7] so that we might be justified by his grace and become heirs in hope of eternal life.

2 Peter 1:9 For whoever lacks these things is blind and shortsighted and has forgotten that he was cleansed from his old sins.

Acts 22:16 And now why do you wait? Rise and be baptized, and wash away your sins, calling on his name.

I made an argument about the last verse in my book, A Biblical Defense of Catholicism (completed in 1996; published in 2003):

The Protestant has difficulty explaining this passage, for it is St. Paul’s own recounting of his odyssey as a newly “born-again” Christian. We have here the Catholic doctrine of (sacramental) sanctification/justification, in which sins are actually removed. The phraseology “wash away your sins“ is reminiscent of Psalm 51:2, 7; 1 John 1:7, 9 [“the blood of Jesus his Son cleanses us from all sin. . . . will forgive our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness”] and other similar texts dealing with infused justification, . . .

According to the standard Evangelical soteriology, the Apostle Paul would have been instantly “justified” at the Damascus-road experience when he first converted (almost involuntarily!) to Christ (Acts 9:1-9). Thus, his sins would have been “covered over” and righteousness imputed to him at that point. If so, why would St. Paul use this terminology of washing away sins at Baptism in a merely symbolic sense (as they assert), since it would be superfluous? The reasonable alternative, especially given the evidence of other related scriptures, is that St. Paul was speaking literally, not symbolically. (p. 39)

Francisco cites my definition:

Sanctification is the process of being made actually holy, not merely legally declared so. [4] It begins at Baptism, [5] is facilitated by means of prayer, acts of charity and the aid of sacraments, and is consummated upon entrance to Heaven and union with God. [6] . . .

But what is the difference between this definition of sanctification and the definition of justification?

They’re very close, as I have said, since our infused justification is essentially how you define sanctification.

Worthy of special attention is the denial of legal declaration, i.e., the denial of the imputation of Christ’s merits to man, a point to which I will return shortly.

Trent didn’t preclude any imputation whatsoever. I have had an article about this topic since 1996 on my blog. It was written by Dr. Kenneth Howell, who obtained a Master of Divinity degree from Westminster Seminary, a doctorate in history, and was Associate Professor of Biblical Languages and Literature at Reformed Theological Seminary in Jackson, Mississippi and Associate Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Illinois. He wrote:

Trent does not exclude the notion of imputation. It only denies that justification consists solely in imputation. The relevant canons are numbers 9-11. Canon 9 does not even deny sola fide completely but only a very minimal interpretation of that notion. I translate literally:

If anyone says that the impious are justified by faith alone so that he understands [by this] that nothing else is required in which [quo] he cooperates in working out the grace of justification and that it is not necessary at all that he be prepared and disposed by the movement of his will, let him be anathema.

Canon 9 then only anathematizes such a reduced form of faith that no outworking of that faith is necessary. This canon in no way says that imputation is not true but only that it is heretical to hold that justification consists solely in imputation.

I am puzzled why anyone would say that extrinsic righteousness might be excluded by Trent. The only righteousness that justifies is Christ’s. But Catholic theology teaches that what is Christ’s becomes ours by grace. In fact Canon 10 anathematizes anyone who denies that we can be justified without Christ’s righteousness or anyone who says that we are formally justified by that righteousness alone. Here’s the words:

If anyone says that men are justified without Christ’s righteousness which he merited for us or that they are formally justified by it itself [i.e. righteousness] [‘per eam ipsam‘], let him be anathema.

Canon 10 says that Christ’s righteousness is both necessary and not limited to imputation i.e. formally. So, imputation is not excluded but only said to be not sufficient.

With regard to imputation, if Trent indeed excludes it, I am ready to reject it. But the wording of the decrees does not seem to me to require this.

How could I become a Catholic if I still thought imputation was acceptable? Because I came to see that the rigid distinction between justification and sanctification so prominent in Reformation theologies was an artificial distinction that Scripture did not support. When one takes into account the whole of Scripture, especially James’ and Jesus’ teaching on the necessity of perfection for salvation (e.g. Matt 5;8), I realized that man cannot be “simul justus et peccator.” Transformational righteousness is absolutely essential for final salvation. . . .

The Protestant doctrine, it seems to me, has at least two sides. Imputation is the declaration of forgiveness on God’s part because of Christ’s work but it is also a legal fiction that has nothing immediately to do with real (subjective) state of the penitent. Now I think the declaration side of imputation is acceptable to Trent but not the legal fiction side. The difference between the Tridentine and the Reformation views, in addition to many other aspects, is that in the latter view God only sees us as righteous while in the former, Christ confers righteousness upon (and in) us.

There is another reason why I think imputation is not totally excluded but is acceptable in a modified form. Canon 9 rejects sola fide but, as we know, Trent does not reject faith as essential to justification. It only rejects the reductionism implied in the sola. So also, canon 11 rejects “sola imputatione justitiae Christi and sola peccatorum remissione.” Surely Trent includes remission of sins in justification. Why would we not say then that it also includes imputation of Christ’s righteousness? If faith (canon 9) and remission of sins (canon 11) are essential to justification, then should we not also say that imputation of Christ’s righteousness is also necessary? . . .

What is wrong with the Reformation view then? It is the sola part. Faith is essential but not sola fide. Remission of sins is essential but not sola remissione. Imputation via absolution is essential but not sola imputatione.

See my related articles:

Council of Trent: Canons on Justification (with a handy summary of Tridentine soteriology) [12-29-03]

Initial Justification & “Faith Alone”: Harmonious? [5-3-04]

Monergism in Initial Justification is Catholic Doctrine [1-7-10]

Salvation: By Grace Alone, Not Faith Alone or Works [2013]

I agree that the sacraments confer grace and that we feed on the body of Christ, but not without the help of faith and freedom. We Protestants reject the passivity of the human being in receiving grace through the sacraments and, although this is not the appropriate place for this debate, I take the opportunity to ask: when the Roman Catholic feeds on Christ, does he not believe that he feeds on Christ? if also of its merits? Or is the Christ of the Eucharist not the crucified, dead and risen Christ? Does the Christ of the Eucharist come without the merits earned by his obedient life and death on the cross? And if he comes with the merits of his obedience and death, how can anyone not be perfectly justified if Christ himself with his righteousness is in us?

We believe that the infinite merits of Christ were received upon initial justification, which is monergistic and includes imputation, as just explained.

Saint Paul says: “And if Christ is in you, the body is dead because of sin, but the spirit lives because of righteousness.” Romans 8:10

That sure sounds like infused, not imputed justification, to me.

To deny the present perfection of justification is to deny the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist and this logical consequence is devastating for the Roman Catholic.

It’s not at all, per the reasoning and Bible passages I have already presented in this reply. Catholics have a moral assurance of salvation, which for all practical purposes, isn’t all that different from Protestants’ belief in a past justification. We simply acknowledge, with Paul, that we have to remain vigilant, so we don’t fall away from faith and grace. Calvinists have the insuperable burden of having to rationalize and explain away the many verses along those lines. I never accepted eternal security or perseverance of the saints (though I came close and thought that only deliberate rejection of Christ would cause apostasy), which is why I was an Arminian evangelical. I was making arguments against Calvinism in the early 1980s. But I’ve also been positively influenced by many great Reformed Protestant theologians.

The idea that there is merit to be rewarded (congruity or condignity) presupposes a self-originating work, . . .

I used the phrase “self-originated works” — in context — with the meaning of “without God’s prior enabling grace.” I was opposing (as the Catholic Church does) Pelagianism and works-salvation but not works altogether, which obviously involve human free will and choice.

To say that there is merit to be rewarded is against Christian ethics from every angle. To paraphrase Luther: there is no merit, either of congruity or of condignity; all merit belongs to Christ on the cross. But the Church of Rome teaches that the person has merit, contrary to what is said: “that God crowns his own merits”.

Yes, St. Augustine wrote that, and it perfectly harmonizes with our conception of merit. I’ve written many articles about merit, as taught in the Bible. Here are some of those:

Catholic Merit vs. Distorted Caricatures (James McCarthy) [1997]

Does Catholic Merit = “Works Salvation”? [2007]

Catholic Bible Verses on Sanctification and Merit [12-20-07]

Our Merit is Based on Our Response to God’s Grace [2009]

Merit & Human Cooperation with God (vs. Calvin #35) [10-19-09]

Scripture on Being Co-Workers with God for Salvation [2013]

The Bible Is Clear: Some Holy People Are Holier Than Others [National Catholic Register, 9-19-22]

God crowns his own merits, not the merit that man has earned; God crowns Christ, and the merits we have are all of Christ and received by faith, not works, which is why we have no merit.

I contend that that’s not what the Bible teaches. The Old Testament refers to “the righteous” 136 times and the New Testament uses the same sense 15 times. Every time that occurs, merit is present: someone has achieved a relatively better status under God, with regard to an attainment of greater grace and righteousness and less sin. They’ve done meritorious actions (all of which were necessarily preceded by the grace of God, to enable them) and have been rewarded for them. That’s merit (and God’s lovingkindness).

I’ve also written about the biblical teaching on differential grace offered by God. Lastly, I would note that Protestants themselves believe in differential rewards received in heaven (see, e.g., Lk 14:13-14; 2 Cor 5:10), which is no different — except for the place it occurs — from our notion of merit. Here are many passages proving that merit is biblical teaching:

Psalm 18:20-21 The LORD rewarded me according to my righteousness; according to the cleanness of my hands hath he recompensed me. [21] For I have kept the ways of the LORD, and have not wickedly departed from my God.

2 Samuel 22:21 The LORD rewarded me according to my righteousness; according to the cleanness of my hands he recompensed me.

Jeremiah 32:19 . . . whose eyes are open to all the ways of men, rewarding every man according to his ways and according to the fruit of his doings;

Matthew 5:20 For I tell you, unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.

Matthew 6:3-4 But when you give alms, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, [4] so that your alms may be in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you.

Matthew 19:29 And every one who has left houses or brothers or sisters or father or mother or children or lands, for my name’s sake, will receive a hundredfold, and inherit eternal life.

1 Corinthians 15:10 But by the grace of God I am what I am, and his grace toward me was not in vain. On the contrary, I worked harder than any of them, though it was not I, but the grace of God which is with me.

Ephesians 6:6-8 . . . as servants of Christ, doing the will of God from the heart, [7] rendering service with a good will as to the Lord and not to men, [8] knowing that whatever good any one does, he will receive the same again from the Lord, . . .

Philippians 2:12-13 Therefore, my beloved, as you have always obeyed, so now, not only as in my presence but much more in my absence, work out your own salvation with fear and trembling; [13] for God is at work in you, both to will and to work for his good pleasure.

1 Timothy 4:16 Take heed to yourself and to your teaching; hold to that, for by so doing you will save both yourself and your hearers.

2 Timothy 2:15, 21 Do your best to present yourself to God as one approved, a workman who has no need to be ashamed, rightly handling the word of truth. . . . [21] If any one purifies himself from what is ignoble, then he will be a vessel for noble use, consecrated and useful to the master of the house, ready for any good work.

What differentiates one man from another is grace, not the works that each one does, and therefore the one to whom God has bestowed more grace is holier, more just, and more pure, for doing good is an effect of being already transformed by grace, not the cause of grace’s transformation.

We agree on differential grace. We Catholics don’t believe that good works cause grace, but that it’s the other way around. We disagree on whether man can get credit or merit for good works. I think it’s perfectly clear in the Bible that we do obtain such merit and reward (see above). We work together with God and He rewards us for so doing. It’s “both/and”: not the false dichotomy of “either/or.”

Works, therefore, cannot be the cause of justification or sanctification, whence we conclude that it is only by faith in Christ that one is justified, and by grace alone are we sanctified, there being no merit on our part.

I’ve shown with 50 Bible passages that works play a central role in determining who will be eschatologically saved. But they are in conjunction with grace and faith. I’m providing tons of Holy Scripture. My proofs are inspired. :-)

I agree that the doctrine of works as the cause of salvation is Pelagianism, but is it not Mr. Armstrong who teaches that faith alone is insufficient to justify man? Is it not Mr. Armstrong who maintains that works are also causes of salvation?

Voluntary grace-originated works in regenerated, initially justified Christians are perfectly biblical, and required in the overall mix to be saved. I’ve shown that, and it hasn’t been overthrown by contrary Scripture (precisely because the Bible doesn’t contradict itself). Pelagianism is completely different. It falsely claims that man can start the process of doing good; but only God can start that process. It’s works without grace, lifting ourselves up by our own bootstraps: nothing that anyone should depend on. We simply don’t teach works without grace. We believe in Grace Alone (as the ultimate cause of salvation and all good things), as Protestants do.

[I]n spite of having already demonstrated it before, I will quote again some verses that prove the existence of a justification before men . . .

If it was done “before,” then I’m sure I answered before, in which case, 1) I need not answer again, and 2) Francisco needs to answer my counter-replies, rather than simply repeat his arguments, and 3) we ought not bore our readers by repeating “old news.” Repetition does not make any argument stronger. It works for propaganda, political campaigns, and television commercials, but not in reasoned debate about Christian theology. It suggests the weakness of one’s case.

I do not question the legitimacy of anyone objecting that justification before God is not acquired by faith alone, but to deny the necessity of a good testimony for men also to consider us righteous is indeed a surprise to me. Does Mr. Armstrong believe that our witness to the world is irrelevant? Does he deny that men also consider us fair when they see our behavior change?

No to both questions (being such a witness myself, as my vocation and occupation); I just don’t think that’s what the Bible is referring to when it refers to justification. When I replied to these arguments that are now being repeated, as I recall, usually context proved my point.

The debate must revolve around our justification before God, whether it is by faith alone, which I claim, or whether it is by faith and works, which Mr. Armstrong claims, but to deny that there is a justification before men is an extreme that cause astonishment. Ask “where is this distinction found in Holy Scripture?” It is the same as saying: there is no teaching in Scripture of the need for a good witness before men, when Scripture says: “You are the light of the world; a city built on a hill cannot be hidden; Nor do you light a lamp and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick, and give light to everyone in the house. Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven.”

The witness is all well and good and quite necessary. I would use the same proof texts for that. But I don’t see that this is justification in any sense. The phrases “justification before men” and “justified before men” never occur in the New Testament (RSV), and it seems to me that they would if this was supposed to be a biblical teaching. Francisco cites another passage:

1 Peter 2:12 Maintain good conduct among the Gentiles, so that in case they speak against you as wrongdoers, they may see your good deeds and glorify God on the day of visitation.

Once again, this is simply successful evangelistic strategy. If anything, it would fit under the Protestant category of sanctification: supposedly completely distinct from justification.

My goal [by citing Calvin] was to bring a definition in line with Reformed theology, so that no one accuses me of inventing concepts or making any inaccuracy about what I am advocating. This is not against the rules of debate. . . . I quote Scripture and I also quote John Calvin in support, not as a foundation of what I believe. I quote John Calvin because I believe what he stands for agrees with Scripture, . . .

I agree. I just cited Strong and Hodges (and Louis Bouyer and Kenneth Howell), so Calvin can also certainly be cited for the purpose of definitions. We have to give each other a little leeway. My rules were designed so that things didn’t get out of hand and go off in all directions.

The same words can have different meanings, and I believe that’s the case here.

I agree again. And we both need to work hard to accurately understand the definitions of the other side.

I claim that there is a deviation of focus here, as my objection has not been answered. My contention is that there is a practical difference whether we believe otherwise, to which Mr. Armstrong responds by making a defense of justification as a process and not by imputation. Mr. Armstrong, to answer my question, should show why there are no practical differences even though there are theoretical differences. Instead, he only ratified the theoretical differences and did not show how these differences do not impose practical differences.

Fair enough. I would answer that the “peace” that Catholics have, within a paradigm of justification and salvation as lifelong processes, is our moral assurance of salvation. I linked to an article about that before, but for the sake of our book I’ll actually cite its words now:

The Catholic faith, or Christian faith is about faith, hope, and love; about a relationship with God and with our fellow man, and faith that God has provided His children with an authoritative teaching Church, so that they don’t have to spend their entire lives in an abstract search for all theological truth, never achieving it (because who has that amount of time or knowledge to figure everything out, anyway?). The true apostolic tradition has been received and delivered to each generation, through the Church, by the guidance of God the Holy Spirit.

We’re not out to sea without any hope or joy, because we’re not absolutely certain of our salvation. God wants us to be vigilant and to persevere. This is a good thing, not a bad thing, because human beings tend to take things for granted and to become complacent. Unfortunately, much of the Protestant theology of salvation (soteriology) caters to this human weakness, and is too simplistic (and too unbiblical).

The degree of moral assurance we can have is very high. The point is to examine ourselves to see if we are mired in serious sin, and to repent of it. If we do that, and know that we are not subjectively guilty of mortal sin, and relatively free from venial sin, then we can have a joyful assurance that we are on the right road.

I always use my own example, by noting that when I was an evangelical, I felt very assured of salvation, though I also believed (as an Arminian) that one could fall away if one rejected Jesus outright. Now as a Catholic I feel hardly any different than I did as an evangelical. I don’t worry about salvation. I assume that I will go to heaven one day, if I keep serving God. I trust in God’s mercy, and know that if I fall into deep sin, His grace will cause me to repent of it (and I will go along in my own free will) so that I can be restored to a relationship with Him.

We observe St. Paul being very confident and not prone to lack of trust in God at all. He had a robust faith and confidence, yet he still had a sense of the need to persevere and to be vigilant. He didn’t write as if it were a done deal: that he got “saved” one night in Damascus and signed on the dotted line, made an altar call and gave his life to Jesus, saying the sinner’s prayer or reciting John 3:16.

The biblical record gives us what is precisely the Catholic position: neither the supposed “absolute assurance” of the evangelical Protestant, the “perseverance” of the Calvinist, nor the manic, legalistic, Pharisaical, mechanical caricature of what outsider, non-experienced critics of Catholicism think Catholicism is, where a person lives a “righteous” life for 70 years, then falls into lust for three seconds, gets hit by a car, and goes to hell (as if either Catholic teaching or God operate in that infantile fashion).

The truth of the matter is that one can have a very high degree of moral assurance, and trust in God’s mercy. St. Paul shows this. He doesn’t appear worried at all about his salvation, but on the other hand, he doesn’t make out that he is absolutely assured of it and has no need of persevering. He can’t “coast.” The only thing a Catholic must absolutely avoid in order to not be damned is a subjective commission of mortal sin that is unrepented of. The mortal / venial sin distinction is itself explicitly biblical. All this stuff is eminently biblical. That’s where we got it!

Moreover, the reason we are so concerned about falling into mortal sin and being damned, is because St. Paul in particular states again and again (1 Cor 6:9-11; Gal 5:19-21; Eph 5:3-6; 1 Tim 1:9-10; cf. Rev 21:8; 22:15) that those who are characterized by and wholly given over to certain sinful behaviors will not be saved in the end.

So we have to be vigilant to avoid falling into these serious sins, but on the other hand, Paul still has a great assurance and hope. All the teaching of Catholic moral assurance can be found right in Paul. Vigilance and perseverance are not antithetical to hope and a high degree of assurance and joy in Christ (Rom 5:1-5; 8:16-17; 12:12; 15:4, 13; Gal 5:5-6; Eph 1:9-14, 18; Col 1:11-14, 21-24; 3:24; cf. non-Pauline passages: Heb 6:10-12; 10:22-24; 1 Pet 1:3-7).

We observe, then, as always, that Holy Scripture backs up Catholic claims at every turn. We have assurance and faith and hope, yet this is understood within a paradigm of perseverance and constant vigilance in avoiding sin, that has the potential (remote if we don’t allow it) to lead us to damnation.

Bottom line: in a practical, day-to-day “walk with Christ as a disciple” sense, Catholics (broadly speaking) are — or can be — every bit as much at peace and joyful and “secure” in Christ, with an expectation of salvation and heaven in the end, as any Protestant. I’ve experienced it myself in my own life. I don’t sit around worrying whether I’ll wind up in hell. I simply do my best by God’s grace and the guidance of the indwelling Holy Spirit to love and follow and worship God and love my fellow man, and share the Good News with as many as I can through my writing. I trust that God is merciful, and I know how good He has always been to me (and now my family): true to His promises and filled with blessings for us that we can’t even imagine: both in this life and the next. All praise and honor and glory to our wonderful God!

Francisco responded to a number of Bible passages that I brought up. He complained that I went off-topic. I did, a little (as I can see now), but I was replying directly to his comment, “This peace will not be obtained if justification is a lifelong process” with a list of passages showing that it is exactly that. If that point is established, then Francisco has to grapple with what he sees as a disconnect between the process of justification and spiritual peace. The first passage he examined was Romans 8:13-17.

What Mr. Armstrong calls justification, I call sanctification. Incidentally, there is no mention of the word justification in this verse.

One doesn’t need the exact word for the concept to be present. The passage refers to “sons of God,” “children of God,” “heirs of God,” and “fellow heirs with Christ”: all of which are perfectly compatible with being justified in the Protestant definition (and much more so than to their category of sanctification). None of those titles would apply to a non-justified person in that schema. So this is a moot point.

This initial grace, which already transforms because it is monergistic (to use the author’s own term), can be rejected. Here, however, we have a logical problem. Pay attention: if it is grace that grants faith, and this initial justification is monergistic, how can man not believe if faith is already in grace? Can a man have faith and not believe? And if man needs not to resist grace so that he can have faith, then this grace needs the concurrence of freedom, not being monergistic, but synergistic.

We agree, which is why Catholics agree with Protestants (particularly Calvinists) with regard to the predestination of the elect. God has to do this initial work. That’s what I’ve been saying over and over. It’s a great area of agreement.

1 – Justification is by faith.

2 – Faith is given by grace.

3 – Initial justification (which must already include faith, because otherwise it could not be justifier) happens monergistically.

4 – Initial justification already includes faith.

5 – It is impossible to have faith and not believe.

6 – Therefore, it is impossible to be a target of grace and not believe, or it is impossible for grace to be rejected.

This syllogism shows the inconsistency of the Roman Catholic argument itself as presented by Mr. Armstrong. If there is an initial justification by a grace that is monergistic, it follows that this grace cannot be rejected because it is faith-giving and without faith there is no justification. If grace is justifying from the beginning, and justification is by faith, it follows that such grace must contain faith from the beginning; therefore, it is impossible to be rejected, for it is contradictory to have faith and not to believe.

*

Scripture definitely teaches that believers can fall from grace (the very thing that Francisco has just declared to be logically impossible). So it’s his logic against inspired scriptural revelation. The latter tells us, via the apostle Paul: “You are severed from Christ, you who would be justified by the law; you have fallen away from grace” (Gal 5:4). Paul can’t state a falsehood about grace. This is inspired, infallible utterance. He didn’t say that such people never had grace, but that they fell “away from” it and, moreover, were (terrifyingly!) “severed from Christ.”

*

He reiterated in Galatians 1:6: “I am astonished that you are so quickly deserting him who called you in the grace of Christ and turning to a different gospel.” Paul also tells the Corinthians: “we entreat you not to accept the grace of God in vain” (2 Cor 6:1). If grace could not possibly be rejected, these statements would make no sense. Therefore, Francisco’s statement, “it is impossible for grace to be rejected” is false; therefore his entire argument collapses. We must be in line with the Bible!

*

To be taken for righteous because of our actions, I say that Scripture is very clear in affirming that good works are not causes of our justification according to the divine point of view, for the Lord Jesus says:

Luke 6:43-45 “For no good tree bears bad fruit, nor again does a bad tree bear good fruit; [44] for each tree is known by its own fruit. For figs are not gathered from thorns, nor are grapes picked from a bramble bush. [45] The good man out of the good treasure of his heart produces good, and the evil man out of his evil treasure produces evil; for out of the abundance of the heart his mouth speaks.”

This is because we are known through our works, but known by whom? For God or for men? Because if we are only known by God when we show our works, then God does not know our hearts, but since God is omniscient, this knowledge does not refer to God but to men. The scholastic maxim that says “Being precedes working” fits very well here, because first we are saints and then we act holy. Saying that good works are causes of our justification before God is the same as saying that working is the cause of Being, which is a logical and biblical absurdity, especially when justification is taken as synonymous with sanctification, . . .

*

I agree that this is before men, but again, why classify it as its own category of “justification before men”? Why not classify it under the Protestant conception of sanctification, since it refers to “good fruit” and producing “good”? I don’t understand why a third category is created. Three chapters earlier, Jesus said a related thing:

Luke 3:9 Even now the axe is laid to the root of the trees; every tree therefore that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. (cf. Mt 3:10; 7:19)

So it turns out that that these good deeds and “good fruit” have a relation to salvation after all. If they are

done, we’re told (

50 times) that they correspond with being

saved. If they’re

not done, then one will be

damned, as in this verse. Protestant soteriology doesn’t fit here in any sense. If it’s justification before men only (not God), it doesn’t save (if I understand the view correctly). But if it’s Protestant sanctification, it is said to

not have anything to do with salvation, either.

*

Meanwhile, the Bible (the sole Protestant rule of faith and standard and source for its theology) consistently states that works done by grace and in faith, play a crucial role in the overall mix of salvation. If fifty passages can’t prove that to a Protestant like Francisco, how many does it

take? 100? 200? How much inspired proof is

sufficient?!

I came up with 200 that refuted “faith alone” in one of my articles. My opponent could only muster up 45 in supposed

favor of that false doctrine. Does that mean that Catholicism is 4.44 times more biblical than Protestantism when it comes to soteriological matters? :-)

*

Francisco then commented at length on this same topic, citing James 3:12; Matthew 11:16-19; and Romans 11:16. Again, I agree that there is a witness before men; I don’t see how that is justification in the secondary Protestant sense. If it’s regarded as such within the Protestant paradigm, it could have nothing to do with salvation, because they’ve already removed works altogether from that scenario. I dealt with the proposed supporting data in James at length in my last reply.

*

Mr. Armstrong highlights a conditional in the verse [Rom 8:17] to ratify his argument: “provided that we suffer with him that we may also be glorified with him.” To which I reply that the conditionality argument does not succeed, since if taken to the extreme, it will place passive potency in God. How can we apply a conditional to a God who knows everything infallibly? How can a God who knows everything say to a man: “If you do well, I will reward you, if you do badly, I will punish you”?

*

He does it all through the Old Testament, and continues in the New. Prophecies were famous for this: “if you do good thing a, good reward x will happen. If you do contrary bad thing b, judgment y will happen.” God is omniscient. All agree on that, and so there is no need to discuss it. The conditionals aren’t directly based on God (He being immutable and omniscient), but on man’s free will choices, which He incorporates into His providence.

*

The only answer is that this question is asked anthropopathically, that is, in a human way, taking into account human ignorance, because it is we men who have the doubt of what will happen tomorrow, not God.

*

We need not posit this (though it, too, is a common biblical motif, that I am often pointing out to atheists, who don’t get it). God rewards those who do good, and (eventually) punishes and (if repentance never occurs) sentences to hell those who reject Him and act badly. That is a theme throughout the entire Bible.

*

Predestination is, of course, it’s own self-contained topic, and one of the most complex in theology. I have written a lot about it (I’m a Congruist Molinist). Presently, it’s off-topic, so I’ll refrain from getting too much into it. The debate is long and multi-faceted enough as it is. Given that, the very last thing we want to get embroiled in is a predestination discussion.

*

[I]n the vector of creatures it is “provided that we suffer with him that we may also be glorified with him.” (Rom 8.17)

*

This need not get into predestination and the timelessness of God, etc. It’s simple: either we willingly suffer with God, or else we won’t be His children, heirs, etc. (i.e., we won’t be saved or in the elect). God knows from all eternity who will do this, so I would say that He simply chooses not to predestine those who won’t. But from where we sit, we either obey Him and suffer with Him or we will be lost. He gives us that choice. Paul uses the very familiar biblical conditional again in asserting: “if by the Spirit you put to death the deeds of the body you will live” (Rom 8:13). We have to do certain things to gain eternal life. It’s not just abstract belief and assent. Faith without works is dead.

*

Francisco tackles 1 Corinthians 9:27, about possibly being “disqualified” (from salvation). He says: “First, this text is not about justification, but sanctification.” Context — as so often in these discussions — is totally against his view, because it’s talking about gaining eternal life: which in Protestant soteriology has to be about justification, not sanctification. In 9:24 Paul states: “Do you not know that in a race all the runners compete, but only one receives the prize? So run that you may obtain it.”

*

What’s the “prize”? Of course it is salvation and eternal life. Protestantism rejects merit, so that can’t be it. Nor can Francisco apply this to rewards in heaven, because they are multiple and various, not singular (which is salvation itself). Then in 9:25 Paul refers to an “imperishable” wreath: which again is clearly talking about eternal life.

John Calvin in his commentary (though he ultimately echoes Francisco’s view) calls it “a crown of immortality.” Therefore (all this taken into consideration), the passage is about justification, and about how it can possibly be lost: which is contrary to Calvinism and perfectly consistent with Catholicism, Orthodoxy, and Arminian / Wesleyan Protestantism.

*

St. Paul only supposes his own ignorance concerning future acts,

*

How can he do otherwise, not knowing the future? How can any of us do otherwise? That’s the point.

*

and from this it does not follow that St. Paul’s future was indefinite to God.

*

Of course it isn’t. Why does this always have to be brought up? It’s not an “either/or” thing, where man is not

nothing because God is supreme. God includes us in His plans, thereby granting us extraordinary dignity. He even

shares His glory with us.

*

Lastly (I will only note this once): just because God knows everything and is outside of time, it doesn’t follow that He caused every particular event, or — more precisely stated — caused it to the exclusion of human free will, which is also present. I pretty much “know” that the sun will rise tomorrow. But when it happens I can assure everyone that I didn’t cause it beforehand. God allows us to make free will choices, so that we are much more than mere robots who can only do what He programs us to do. His granting us free will to choose right and wrong; to follow or reject Him, doesn’t detract from His majesty or sovereignty in the slightest. I think it makes His providence even more glorious.

*

St. Paul is admonishing his brethren in the Church at Corinth, taking himself as an example, just as Christ himself was tempted even though he could not sin.

*

That’s a failed analogy. Jesus could not possibly be successfully tempted. The devil (in his stupidity) could only try. But Paul could possibly fall away: because he said so.

*

Now, to say that salvation can be lost because the apostle declares his obligations, his submission to the law and also the possibility of being disqualified, does not mean that this can happen in reality, at least not from the divine perspective,

*

That’s an eisegetical analysis. Of course it can happen, because Paul said it could, and he is an inspired writer. The language is very concrete, practical, phenomenological; not abstract and supposedly talking about deep and inexplicable mysteries of the faith. Paul’s giving solid, realistic advice for day-to-day Christian living. It’s also possible from the divine perspective, because the Bible says that He doesn’t wish “that any should perish, but that all should reach repentance” (2 Pet 3:9). Yet many do perish, because many choose to reject His free offer of grace for salvation . This doesn’t surprise God, because He can’t be surprised, knowing everything and being outside of time.

*

for if that were so, I would could say that Christ could sin, for He Himself says, “Lead us not into temptation” (Luke 11:4).

*

He also got baptized, even though He had no need to, since it regenerates and follows repentance and He had no need for either. Some things He did simply as an example.

*

The simple fact that Christ was tempted implies a possibility of a fall if we look at the angle in which Mr. Armstrong interprets these verses.

*

Nonsense. He couldn’t and can’t fall because He is God, and therefore impeccable. I’ve never claimed nor remotely implied otherwise. I defend the classical attributes of God; always have in my 41 years of apologetics.

*

Otherwise it would not be temptation, it would be drama, but Christ cannot really fall, so it doesn’t take a real possibility of a fall to be admonished and to strive not to. No one was harder than Christ, no one prayed more than Christ, no one suffered worse temptations than Christ, and yet none of this means that Christ could fall from grace, even as Paul says of himself that he strives not to.

Jesus never stated that He could fall into sin, as Paul does, so this doesn’t fly. There’s no valid comparison. Paul is a fallen creature (who even once killed Christians). He wrote: “I am the foremost of sinners” (1 Tim 1:15) even after His regeneration. Jesus is God and did not and could not ever sin. Quite a contrast, isn’t it? Yet Francisco compares them and acts as if Paul could never fall, even though he repeatedly says that he (or anyone) conceivably or possibly or potentially could.

According to the teaching of St. John, those who come out of us, only manifest, reveal that they were not of ours (1 Jn 2.19).

*

In that particular instance they were not, because these were extreme sinners: described as “antichrists” in the previous verse. Other passages, that I have produced, prove that apostasy is entirely possible, and should be vigilantly avoided. Francisco uses the same argumentative technique (refuted above) for 1 Corinthians 10:12. He then uses the same sweeping “can’t possibly happen” special pleading excuse to dismiss nine more texts that I brought up, concluding with a misguided triumphalism: “The same explanation can be applied to all these texts, which prove nothing from Mr. Armstrong’s point of view.”

*

For the elect, the fall is not the loss of salvation, but a means of improvement, . . .

*

The elect cannot fall away by definition, because the word means that they are eschatologically saved, and predestined to be so.

*

The system of justification by a process caused by good works and faith depends on perfect faith and an immeasurable amount of perfect works.

*

Not at all. In the end, the Catholic needs to simply be free of mortal, serious, grave sin: entered into with a full knowledge and consent of the will. Failing that, the baptized Catholic who has been receiving grace through sacraments, too, his or her whole life, will be saved. It may, of course, be necessary (as with most of us) to be purged of remaining non-mortal sin in purgatory. But there is no necessity at all for “an immeasurable amount of perfect works.” That’s simply an absurd caricature of our view: suggesting that it has been vastly misunderstood. Or it is a failed, noncomprehending attempt at the reductio ad absurdum.

*

If not even St. Paul attained justification, am I or anyone better than St. Paul? If St. Paul is strictly speaking of justification, as Mr. Armstrong says, when will I have peace with God?

Here’s what Paul wrote shortly before his martyrdom:

2 Timothy 4:6-8 For I am already on the point of being sacrificed; the time of my departure has come. [7] I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith. [8] Henceforth there is laid up for me the crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous judge, will award to me on that Day, and not only to me but also to all who have loved his appearing.

Paul thought exactly as Catholics do. He wasn’t worried about his salvation. He was quite certain of it. It sounds to me like he was perfectly at peace. At the same time he didn’t pretend that it was all accomplished many years before when he was supposedly justified for all time in an instant. He says nothing about that or anything remotely like it. He refers to a process: a “good fight” and a “race” that he “finished”: in which he had “kept the faith.”

*

If he was a good proto-Protestant, he would have, I submit, written something along the lines of: “I was justified by faith alone on the road to Damascus. Henceforth there is laid up for me the crown of righteousness, . . .” That’s Protestant theology: devised in the 16th century, but it’s not Pauline theology.

*

When can I say that “we have peace with God through faith” if that peace is conditional on a series of good deeds I have to do?

*

After one has examined himself and made sure no conscious serious sin is being committed, and particularly after confession and absolution. The peace is not conditional on being perfect, and even ultimate salvation is based on not being in serious sin: as Paul warns about (passages that refer to sins that prohibit one from heaven). As I contended above, Catholics have just as much peace and joy and assurance of salvation as any Protestant: who is no more “certain” of salvation than we are, since he or she doesn’t infallibly know the future. All that any of us can do is to make sure we are not involved in serious sin.

*

From beginning to end is faith. Works in the divine perspective are the fruits of an already holy man, who sanctifies himself more as he receives more grace. It is totally denied in Scripture that good works are causes of sanctification, justification, or glorification.

*

Fifty Bible passages directly contradict this erroneous understanding. Francisco (amazingly enough) tries to dismiss my fifty passages with a

non sequitur / red herring:

*

Then follow Mr. Armstrong’s quotations of several biblical verses that deal with how men were judged for their sins in the past, as if this proved that the merits won by Christ on the cross depended on the concurrence of good works to be effective. . . .

*

As in the order of execution, merits precede glorification, demerits precede disgrace, and so everyone who speaks from a human perspective narrates a cause and effect relationship as seen by the human eye. This serves for the interpretation of other verses. . . .

*

A number of verses, absolutely all suffering from the same problem, are quoted by Mr. Armstrong. Certainly, if they all suffer from the same problem, by answering just one, I will have knocked out all the others.

*

But after making this claim, he does at least offer some specific criticisms. He attempts to turn very simple, easy-to-understand verses into (for lack of a better term) “abstract Calvinist philosophical entities.” But the Bible is not a philosophical treatise. That’s the problem. 1 Samuel 28:16, 18: my first example of fifty of works related to salvation, is very simple: God “turned away” from King Saul, so that he was damned. Why? It’s because Saul had “not obeyed the voice of the Lord.” He didn’t obey (not just didn’t have faith) and so was lost. There is no need or relevance to apply abstract philosophy and the sublime theology of God to that in order to dismiss its plain meaning: disobedience (i.e., evil acts) led to damnation. God gave Saul freedom of choice, and he followed it and chose to reject God.

*

Some of them do not even deal with sanctification or justification, for example:

Ecclesiastes 12:14 For God will bring every deed into judgment, with every secret thing, whether good or evil.

The text deals with the final judgment.

*

*

It is true that not everyone achieves justice here on earth. The rest of the texts are texts that deal with the order of execution, they are admonitions, pastoral advice, which have nothing to do with the proposed theme, because the need to do good works was not denied at any time by me.

*

It has everything to do with the theme. Francisco denies that works have anything at all to do with salvation. The final judgment has to do with final salvation. This is one of fifty passages concerning it, whereby “faith alone” is never ever mentioned. Why? This passage is again talking about “deeds” (i.e., good works). It certainly implies that they play a big role in whether a man is saved or not.

*

Mr. Armstrong must show how these verses prove that a good work is the cause of salvation, sanctification, or justification . . .

*

The fifty taken together overwhelmingly show that good works play a very important role in the whole equation.

*

We are judged primarily by what we are, secondarily by what we do.

*

In the biblical worldview, the two cannot be separated. We do according to what we are. “The good tree produces good fruit,” etc. But if we are to distinguish, the fifty passages I compiled appear to reverse this order, by placing what we do front and center in the matter of the final judgment and salvation or damnation following, based on what we did with the grace He gave us. This simply can’t be ignored or dismissed. The evidence is too relentless and powerful.

*

That’s why even an atheist who does good works cannot be saved, because good works do not cause salvation, but who we are.

*

That’s not what Paul states:

Romans 2:6, 13-16 For he will render to every man according to his works: . . . [13] For it is not the hearers of the law who are righteous before God, but the doers of the law who will be justified. [14] When Gentiles who have not the law do by nature what the law requires, they are a law to themselves, even though they do not have the law. [15] They show that what the law requires is written on their hearts, while their conscience also bears witness and their conflicting thoughts accuse or perhaps excuse them [16] on that day when, according to my gospel, God judges the secrets of men by Christ Jesus.

Personally, I think it follows from this that even an atheist may possibly be saved (I’m not saying it would be easy), based on what they know and what they do with that knowledge, following their conscience, which “bears witness” and may “excuse” them on judgment day. The good thief was saved; why not an atheist, too?

A bad Christian may have fewer good works than an atheist, but the bad Christian is the one who goes to heaven, not the atheist, because it is Christ’s merits that conquer heaven, not what I do.

That’s not what the Bible teaches; as I have massively shown, and will continue to in Parts 2 and 3 of this Round 3. The lax, antinomian-type Christian may very well lose his or her salvation, seeing that even the great St. Paul stated that he had to be vigilant in his own case.

2 Kings 22:13 is dismissed with more mere philosophical fine points of theology proper, which isn’t exegesis. It’s simply application of a prior Calvinist presuppositionalism to every single passage. In the final analysis, we’re not discussing Calvinism’s well-known view of God, but how one is justified and what it means. This passage shows that God was angered because certain of His people disobeyed Him (which entails the absence of good works, which would please God): the same theme as always in the Bible.

Psalm 7:8-10 is dismissed by relegating it to “man’s . . . perspective”: which in Calvinism always seems to amount to very little significance. But it can’t be so easily dismissed. The same Psalms played a role in the messianic prophecies. Jesus quoted one (Ps 22) from the cross. They can’t be ignored simply because a man wrote them. These men (David, mostly: the man “after God’s own heart”) were inspired by God when they wrote. We learn the same thing again. God “judges . . . according to my righteousness” (not proclamations of faith). God “saves the upright in heart.” All of this can’t be squared with “faith alone.” It fits in with it about as good as a truck tire fits a compact car.

The text is a prayer; thus, it deals with the human drama, it does not deal with soteriological metaphysical relationships.

Sure it does. By God’s providence, it became part of inspired, infallible revelation. It teaches how a man is saved, and as usual, it’s harmonious with Catholic, not Protestant teaching.

He asks about my text Psalm 58:11: “How does this prove that justification is by faith and works?” It does because it states: “Surely there is a reward for the righteous”. It’s not one of the most compelling texts in my collection, but nevertheless it shows yet again, even at this early stage of salvation history, that rewards from God come as a result of a person doing good works and being righteous (and yes, having faith too: implied), but not by faith alone.

Francisco then dismissed and ignored nine of my texts, by saying, “All warning texts, which prove nothing against the doctrine of justification by faith.” In so doing, he has violated our agreed-to third rule of this debate:

Both of us should try to actually interact point-by-point rather than picking and choosing; a serious debate where all the opponent’s arguments are grappled with.

Francisco then tackled the important text of Matthew 7:16-27. He wrongly thinks that he can casually dismiss this, too, without seriously examining it and engaging in a true debate about its meaning, by saying, “it proves that we know the tree by its fruits, but God already knows the tree before the fruits appear.” It’s utterly irrelevant to our discussion that God knows what men will do. They are still judged when they disobey Him. Parents know that almost certainly a strong-willed two-year-old will often disobey orders to not run in the street or be noisy in church. They still discipline the child when he or she disobey, and it has no relevance to point out that they “knew” the infant would disobey. The point is that disobedience gets punished.

*

The passage is a tour de force against faith alone. The fruitless tree is “thrown in the fire” (hell). There must be fruit; otherwise, the danger of damnation is quite possible. But Protestantism relegates this fruit to purely optional sanctification: having nothing directly to do with salvation. The fair-minded, objective person must make a choice: biblical teaching, or Protestant teaching that blatantly contradicts it. Jesus warns that saying “Lord, Lord” (similar to saying “faith alone” like a mantra) will not necessarily save one.

*

Rather, it is (you guessed it!): “he who does the will of my Father who is in heaven.” Faith alone can’t cut it. It doesn’t make the grade. It fails the divine test. The one who does these things will be like the man who builds a house “founded on the rock” which “did not fall.” But the one who doesn’t do what Jesus commands will be in a house that falls. Everything is works, here, never faith alone. No one who didn’t already have his mind up, no matter what, could fail to see this. To not see it is like looking up in the sky on a clear day in summer at noon, and not being able to locate the sun.

*

Francisco then ignored no less than 22 (44%!) more of my fifty passages, which again violates our agreement to engage each other point-by-point (No. 3 in the suggested rules). I insisted on that rule precisely because I know from long experience that Protestants quite often engage in this sort of selective, pick-and-choose response. The only good thing about it is that this reply can be shorter. I’m already at nearly 12,000 words. Francisco stated as his reason for the mass dismissal:

*

Redundancy and errors are repeated in each approach, relieving me of the obligation to address each verse in particular. Everyone, absolutely everyone, falls into the same interpretive errors as those commented on.

*

Calvinists, too, are notorious for the droning sameness of their arguments. I could just about make them myself, they are so familiar.

*

After this flurry of texts that prescribe the good Christian way of living, my question remains open: “How many good works must I do to be righteous before God?”

*

I answered that earlier. It’s the wrong question to ask and presupposes caricatures of Catholic soteriology.

*

By quoting the verses, Mr. Armstrong showed that Jesus and the apostles warned us against evil and encouraged us to do good works, but how does that answer my question?

*

It doesn’t answer that question. These passages deal with the question of whether faith alone is a biblical concept and the singular way to salvation or not. The passages massively refute faith alone, which is the substance of Protestant justification (at least on our end).

*

From the verses quoted, then, in an attempt to show how many good works we must do in order for God to count us righteous,

*

That’s not what my attempt was. Rather, it was to show that in every case having to do with the criterion God uses to declare us saved or not, works play a central role, and faith alone never plays any role at all. It’s a decisive, compelling, unanswerable refutation of faith alone.

*

Francisco then partially responded to my summary of fifty attributes that the Bible teaches are connected with being saved at the last judgment. I introduced them as follows:

[H]ow would we properly, biblically answer the unbiblical, sloganistic question of certain evangelical Protestants?: “If you were to die tonight and God asked you why He should let you into heaven, what would you tell Him?” Our answer to his question could incorporate any one or all of the following 50 responses: all drawn from the Bible, all about works and righteousness, . . .

The first on the list was “I am characterized by righteousness.” Francisco answered by asking: “are we righteous because we do good works, or do works manifest our righteousness?” The answer is “both” but in any event, that has nothing to do with the gist of that list of mine. Whatever the answer to his question is, it remains true that this (one of fifty things) is one of the aspects that the Bible says contributes to our salvation, and why God should let us into heaven (according to direct Bible passages).

*

2) I have integrity.

*

3) I’m not wicked.

*

Does that mean not even a trace of evil? Absolute perfection?

*

The answer is, of course, “no.” But the counter-reply is again a non sequitur and attempt to change the topic. He’s looking at the DNA of the bark of one tree in the forest and missing the forest for the tree; focusing on irrelevant minutiae. I’m looking at the larger view of the whole forest and addressing one common Protestant theme: “If you were to die tonight and God asked you why He should let you into heaven, what would you tell Him?” His answers to #4 and #5 repeat the same misguided error. He is by that point discussing an entirely different topic, which is absolutely lousy in terms of being good debating technique.

*

6) I have good ways.

*

Good manners according to which culture?

*

Good ways somehow came out as “manners” in the translation to Portugese. “Good ways” is simply referring to being good and righteous, rather than a thing like manners that is indeed culturally relative. It looks like I substituted “good ways” for “doings” in Jeremiah 4:4, because we don’t say in English, “we have good doings.” It’s still the same thought.

*

He then dismissed #7-17 with one irrelevant, legalistic comment: “How many hungry do I need to feed?” That’s not the point at all, which is that part of what gets us into heaven is willingness to feed the hungry (compassion, love). God isn’t going to say at the judgment: “well, you only fed 1,298 hungry people instead of my quota for salvation, which is 1,300, so sorry, you don’t live up to my requirements and have to go to hell.”

*

That’s neither how God acts (He looks at the motivations and intents of our heart, which only He fully knows), nor a teaching that appears anywhere in the Bible or Catholic moral theology. To frame the issue in this way clearly presupposes — as I have noted before — a gross caricature of Catholic soteriology. Francisco needs to understand why this point or any of my other ones was raised in the first place (context), rather than simply reply over and over with “gotcha!”-type queries. This is also the third violation of #3 of the initial rules: answering point-by-point.

*

He engaged in the same wrongheaded legalism in individual counter-questions for #18-22, then grouped together #23-28 and did the same thing. He grouped #29-34, and seemed to ignore #29-32, in his response, which appeared to be to #33 and #34:

*

33) I’m unblamable in holiness.

34) I’ve been wholly sanctified.

This point is important, for it signifies a total absence of sin, something that, according to Mr. Armstrong, not even the apostles achieved, as they were always admonishing and placing themselves as those who might fall.

As I noted at the beginning of this list, they were “all drawn from the Bible”: from my list of fifty passages having to do with the final judgment. So that is the case here. This isn’t me pulling arguments out of a hat. They came right from express statements of Scripture; in this case the following:

1 Thessalonians 3:12-13 . . . may the Lord make you increase and abound in love to one another and to all men, as we do to you, so that he may establish your hearts unblamable in holiness before our God and Father, at the coming of our Lord Jesus with all his saints.

1 Thessalonians 5:23 May the God of peace himself sanctify you wholly; and may your spirit and soul and body be kept sound and blameless at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ.

According to St. Paul, then, such a sublime level of holiness is indeed possible. He prays that the Thessalonians can achieve it by the time of the Second Coming. Most of us won’t achieve it in fact, but it’s theoretically

possible. One web page collected nine Bible passages about

being holy like God is holy. Seven are in the Old Testament, but that is still inspired Scripture, and the Scripture of Jesus and the apostles before the New Testament was compiled. Two are in 1 Peter 1:15-16, with one of the two citing the Old Testament. The above two passages reflect the same thought, and 1 Thessalonians 5:23 is remarkable in that it refers to the notion that God could “

sanctify [us] wholly.” The royal commandment urges us to equal Jesus in love:

John 15:12 This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you. (cf. 13:34)

Paul again states in Ephesians 1:4 that we should be “we should be holy and blameless before him.” My list numbers 33 and 34 merely repeated what the Bible already taught.

*

36) I know God.

*

The problem is that good works do not prove that a person knows God, there are many atheist philanthropists.

*